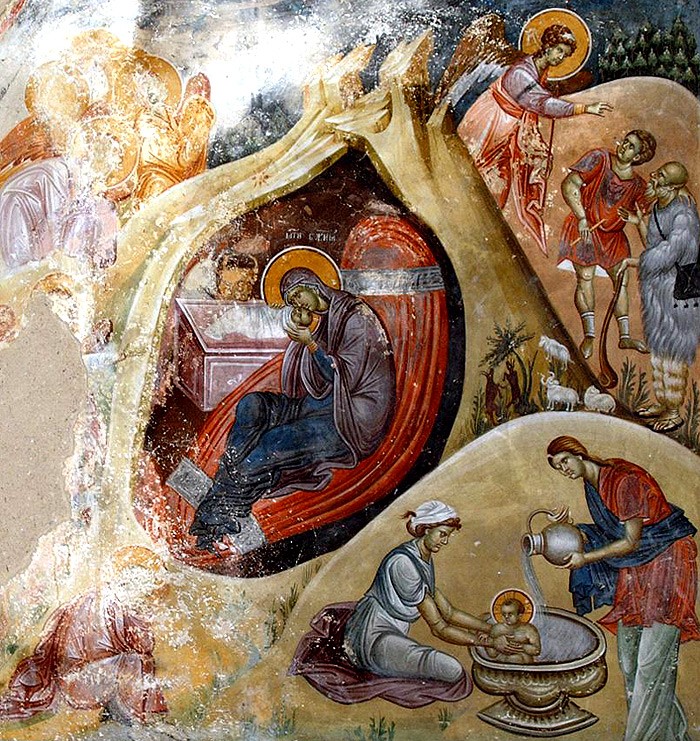

Icon of the Nativity, Studenica Monastery.

Icon of the Nativity, Studenica Monastery.

Fallen Leaves wishes its readers, whoever they may be, a merry Christmas according to the Julian calendar.

We have written before about God’s love for man, but this time, maybe we can start from the other side. For those who haven’t personally experienced any form of religious fervor, perhaps it might be easiest to understand the need for religious faith through love. Someone who has fallen deeply in love, at least at one time in his life, has already felt some form of religious feeling.

It is not a new thought. Plato equated love with the search for immortality:

from the “Symposium”

For Plato, this becomes the common element between physical and non-physical love. Literal childbirth is replaced by the gestation and birth of thought: “Those who conceive spiritually, for there are those, she said, who are pregnant in soul more than in body, precisely because it is more typical for the soul than the body to conceive and become pregnant. What should gestate in the soul? Reason and other virtues… Whosoever, being divine in spirit, becomes pregnant with these things from youth, will also wish to develop and give birth to them at an advanced age. And such a one, I think, will always search for what is beautiful, in order to give birth in it, for it is impossible to give birth in what is ugly. Being the pregnant one, he will love beautiful bodies more than ugly ones; and if he should encounter a beautiful, noble and gifted soul, he will greatly love both one and the other[.]” The birth of virtue then brings one closer to immortality (according to Diotima) than the birth of children. The philosopher “must first learn to love one body and give birth to wondrous speech.” The next step is “to love all beautiful bodies, and reduce that strong love toward a single one,” then to “value beauty in souls more highly than in bodies,” and finally, “approaching the end of the erotic, [to] suddenly see something marvelous in its nature — the same beauty, Socrates, for whose sake all of the earlier labors had been undertaken. First, it always exists and is neither born, nor dies, nor increases, nor diminishes; furthermore, it is not something that is beautiful in one way and ugly in another, or sometimes beautiful and other times ugly, or beautiful for one and ugly for another, or beautiful here and ugly there, or beautiful for some and ugly for others. This beauty will not appear as a certain face, or hands, or anything else pertaining to the body, or as thought or knowledge, or as something existing in something else, for example in an animal, in the earth, in the sky or in another object, but as something existing by itself, always with itself in harmony.”

This abstract beauty, or the Platonic idea of beauty, takes on the qualities of divinity — it is unchanging, eternal, and exists independently of all things. Perhaps it is the only truly immortal entity in the universe. Everything in Plato is hierarchically ordered, including the ascent toward true beauty, so one could easily attempt, if one wanted, to derive the existence of all other ideas from this one. Love becomes the path that leads the philosopher to the revelation of beauty as an idea.

But, in so doing, it ceases to be love. The end goal, in Plato, is philosophical contemplation. The philosopher does not require a response from the idea of beauty, he simply sees it. And, since all living bodies and souls have fallen away over the course of the journey, he is the only individual remaining. Having achieved or at least touched immortality, he is in eternal solitude. For Plato, that is happiness. But it is not love. Love, above all, is the painful yearning for Another — a second individual consciousness, which will never become fully knowable, which can never be fully mastered, which always retains the capability to refuse contact with you, no matter how close you come to it. The true religious element of love does not lie in the understanding of abstract, impersonal beauty. It appears when you are on your knees, calling to someone who will not be able to hear you. You will not need to ask then why religious believers feel compelled to prostrate themselves, to keep long vigils, and to mortify their flesh. It will all make sense to you. You will discover on your own every religious ritual that has ever existed. And if, by some chance, your love should be reciprocated, you will understand the concept of miracles — because, in a world where no one cares about anyone else, even the slightest trace of sincere interest becomes a precious, improbable gift.

The first experience of the awakened individual is joy. One takes pleasure in feeling one’s own uniqueness, one’s thoughts taking shape and soaring in an instant. But this feeling is short-lived. It is quickly replaced by unbearable loneliness, because, if you are truly a one-of-a-kind genius, completely unlike anyone else who has ever lived, then it inexorably follows that you are condemned to be alone forever, precisely for that reason. The more pronounced your individual consciousness, the more trapped you will be inside yourself. So much to offer, but no one to offer it to — a sacrifice that no one wants or needs. The ascent toward Platonic beauty means nothing when there is no one with whom to share it. Platonic beauty will not love you back.

The defining human experience is the painful need for contact outside the self, and religious faith is the starkest expression of that need. It is not at all a consolation; if anything, the anxiety of earthly love should be intensified. God is Another in an absolute sense. It is impossible to fully understand even another person, and yet the human mind is limited, whereas the mind of God is infinite. If another person has the freedom to reject you, imagine then God’s absolute freedom not to answer. The feeling of abandonment is often described in monastic literature. No sacrifice will compel God to respond, and He does not really require it — spend enough time alone, and you’ll be ready to make it of your own accord. But, at the same time, just as the love of another person is an unimaginable gift, an expression of their kindness, imagine then the love of God, freely given. And while we cannot even cross the divide between ourselves and another human being, God is able to overcome the distance between His consciousness and ours, willingly taking on the limitations of physical existence, and thereby revealing the beauty in it. The world is no longer completely cold. There is at least the possibility of holiness in human feeling. Love can exist insofar as it is able to mirror the sacred self-effacement of Divine love.

Metr. Anthony of Sourozh in 1970

Christ is Born! Христос раждается! Христос се роди!

Christ is Born! Христос раждается! Христос се роди!