“Here are the five greater signs [of decay]: the once-immaculate robes are soiled, the flowers in the flowery crown fade and fall, sweat pours from the armpits, a fetid stench envelops the body, the angel is no longer happy in its proper place.”

(Angel, 53)

(Conclusion. Continued from part 3.)

Mishima completed The Decay of the Angel on the morning of November 25, 1970. That same day, he “staged a violent incident at the SDF headquarters at Ichigaya in central Tokyo,” taking the commandant hostage, then attempted to exhort the soldiers “to join him in a revolt to overturn the constitution,” and finally “returned inside the building and, with the assistance of his students, committed suicide by seppuku.” (Rankin, 171) But we already discussed Mishima’s nationalism. What matters now is that nowhere in Angel is there the slightest hint of anything political, nor the most remote suggestion of this violent end. Continue reading →

“Everything hurts in the tree of human life.” (Leontiev, 189)

“Everything hurts in the tree of human life.” (Leontiev, 189) Fresco of the Resurrection. Mikhail Nesterov, 1909.

Fresco of the Resurrection. Mikhail Nesterov, 1909.

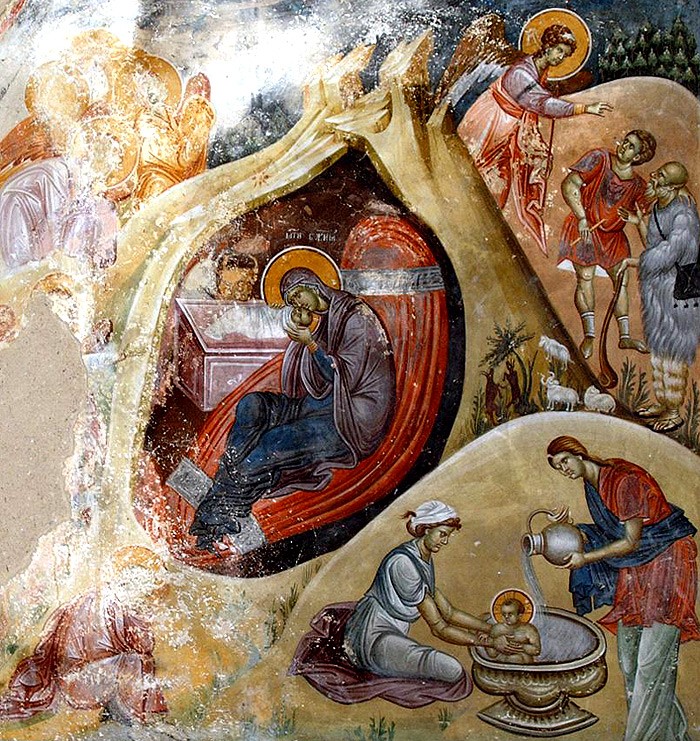

Icon of the Nativity, Studenica Monastery.

Icon of the Nativity, Studenica Monastery.

Pskov Caves Monastery.

Pskov Caves Monastery.

Fresco of the Nativity, from a 10th-century

Fresco of the Nativity, from a 10th-century

Icon of the Trinity.

Icon of the Trinity.