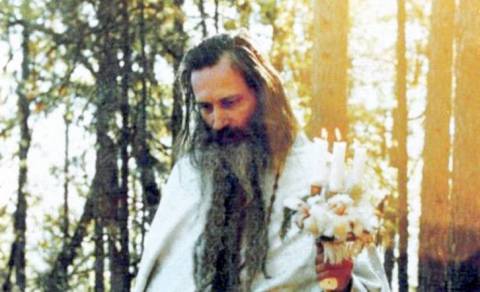

Fr. Seraphim (Rose) serving the Paschal Liturgy.

(Continued from part 7.)

In 1977, Fr. Seraphim was ordained a priest. This dramatically changed the focus of his life — he no longer had much time to theorize about the apocalypse or to partake of silent contemplation, but now devoted himself to the increasing numbers of pilgrims and converts that proved willing to come to remote Platina. He continued to work on The Orthodox Word, but never got a chance to finish Genesis, Creation, and Early Man, and did not write any other books beyond the three that we have examined.

This dimension of Fr. Seraphim’s life is difficult to see only from his published writing, but it was Fr. Seraphim the priest, not Fr. Seraphim the writer, who had the greater and more lasting significance. From the outside, it may seem that he did not “do” much of anything — “only” serving Liturgies, answering questions, fussing over the spiritual condition of the people in his care (who, like countless novices throughout the ages, were often inclined to come asking for guidance over every minor emotional impulse), and staying up nights praying for them.

Fr. Seraphim had always envisioned a missionary aspect to the Platina monastery; that was the main motivation for publishing The Orthodox Word, which, as you may recall, involved considerable hardship. Despite his deep reverence for the Russian tradition, which for him had been personified by St. John of Shanghai, Fr. Seraphim did not want to join any existing monastic community in ROCOR, and did not see himself as following in the footsteps of St. John or any of the Russian hierarchs or theologians whom he admired. In all of his writing, he valiantly defended Orthodox tradition, but at the same time he must also have believed that he was helping to bring forth something in some way new, and entirely American. When recalling how they first bought the Platina land, Fr. Herman (Podmoshensky) ascribed to him the dream “to bring Orthodoxy into the midst of these simple people, into the land of the cowboys!” (Damascene, 344)

Once converts started to accumulate around him, Fr. Seraphim did his best to educate them in traditional Orthodoxy, often using the examples of Russian saints (St. Herman Press published an entire collection of Lives of Saints translated from Russian by Fr. Seraphim, under the title The Northern Thebaid), but he also encouraged them to take charge of their spiritual development and form their own small communities instead of attempting to “fit in” at the nearest ROCOR parish. “In a series of articles he wrote on the Typicon of Church services, Fr. Seraphim tried to dispel what he called ‘the popular misconception that Orthodox Christians are not allowed to perform any Church services without a priest, and that therefore believing people become quite helpless and are virtually “unable to pray” when they find themselves without a priest — as happens more and more often today.’ After quoting an appeal from Archbishop Averky for Orthodox Christians to come together in public prayer even where there is no priest, Fr. Seraphim concluded: ‘This practice can and should be greatly increased among the faithful, whether it is a question of a parish that has lost its priest or is too small to support one, of a small group of believers far from the nearest church which has not yet formed a parish, or a single family which is not able to attend church on every Sunday and feast day.” (Damascene, 501) Of course, this should be properly understood — Fr. Seraphim was referring to the so-called “lay service,” a kind of abridged version of the Liturgy, “served” by laymen, that does not involve Confession or Communion and thus can never fully substitute for a Church service; he is further defending it as a traditional practice by citing Archbishop Averky (Taushev), a leading ROCOR theologian who shared all of Fr. Seraphim’s anti-ecumenist convictions and strongly upheld Church authority. But nonetheless, the practical implication, of which Fr. Seraphim was surely cognizant, was that American converts to Orthodoxy should expect to (and should be instructed to) set out on their own. Considering how deeply he himself had delved into Russian culture, it is shockingly humorous to hear, from one of his spiritual children, “More than once Fr. Seraphim wrote/said: ‘Do not learn Russian. If you know Russian you’ll hear all the gossip and be tempted to participate in it. And don’t join a parish council anywhere. Avoid parish politics like the plague!’ Of course my family and I were encouraged to attend Liturgy in various parishes and receive the Holy Mysteries, but we were discouraged from participating in other parish activities, which [Fr. Seraphim] felt would derail me from the ‘calling’ he believed had been sent to me by God — i.e., missionary work through writing, teaching, publishing.” (502-503)

It is difficult to say exactly how much Fr. Seraphim was hoping to accomplish with that, but in any case, Americans did come to him, and some of them felt inspired to make choices that lasted for the rest of their lives. One such person was Craig Young, who in his early twenties became disillusioned with his Roman Catholic background and by chance (or “chance”) met Eugene and Gleb in San Francisco one day. Having been deeply moved by St. John’s funeral, he eventually converted to Orthodoxy (taking the name Alexey) together with his wife. Living in a very small town near the California/Oregon border, far from any ROCOR parish, Alexey basically single-handedly created his own parish, or rather, it grew around his household — it was for his benefit that Fr. Seraphim wrote about the lay service. In 1979, Alexey also became a priest, and continued to serve for thirty years after Fr. Seraphim had left this world.

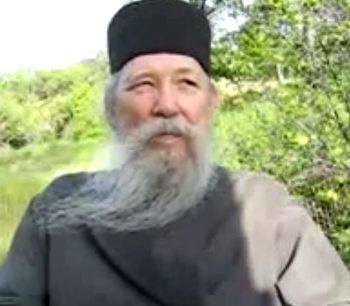

Fr. Ambrose (Young) in 2013.

Fr. Ambrose (Young) in 2013.

Later, after the death of his wife, Fr. Alexey became a monk with the name Ambrose, and took the vows of the Great Schema, the highest and strictest degree of self-renunciation in Orthodox monasticism. In the late 2000s, Hieroschemamonk Ambrose (Young) was diagnosed with Alzheimer’s disease; in 2011, he offered the following thoughts about it:

“From a purely spiritual standpoint I want to share with you the insight I believe God gave me from the time of my diagnosis. My greatest and overriding sin — indeed, even vice — has always been pride. Pride of mind, of ‘knowing better’ and judging others inappropriately, sometimes thinking of them as being less than I am. This is a most grievous sin, and one that many people don’t even recognize in themselves, but it is the one sin that will, above all, consign us to hell if we don’t overcome it! It was the sin of Satan, the sin of Adam and Eve… Now the Lord has offered me a chance to mortify and humble down that pride, by accepting without complaint the slow crumbling of my mind. And I do accept this, with my whole heart, even if with the occasional tear, as a gift from Him for my salvation. So it sometimes ‘feels’ as though this dying of various parts of my mind is also a dying of self…isn’t that the purpose of spiritual life, after all, anyway? The Lord looked down and saw that I wasn’t going to do it any other way…I see this as a great, if sometimes painful, blessing!”

As of this writing, Fr. Ambrose has long retired from priestly duties, and does not maintain a public presence.

St. Xenia Skete, Wildwood, CA.

St. Xenia Skete, Wildwood, CA.

In 1975, an acquaintance of Frs. Seraphim and Herman “came to the Platina hermitage and told the fathers that she was thinking more and more of establishing a quiet life in the country. She had found another young woman with the same interest, a student of opera singing named Barbara McCarthy… Barbara, who had converted to Orthodoxy in 1968, had been inspired by desert monasticism ever since reading the early Orthodox Word issue on the wilderness sketes of Canada. Giving up her opera career, in 1972 she had made a pilgrimage to these sketes… Less than two weeks later Barbara returned to the hermitage by herself, soaking wet after having walked halfway from Redding and having spent the night in the wilderness.” (Damascene, 580-581) Barbara’s ascetic vision was if anything even more austere than that of Fr. Seraphim:

(Damascene, 582-583)

In 1978, Frs. Seraphim and Herman were able to buy some land a few miles from Platina in which Barbara and several other women established what is now called the St. Xenia Skete. In 1980, Fr. Seraphim tonsured Barbara into monasticism — in keeping with his overall unwillingness to keep his spiritual children tethered to Russian culture, he gave her the monastic name Brigid, after a pre-Schism Irish saint.

Fr. Seraphim and Bishop Nektary (Kontzevich).

Fr. Seraphim and Bishop Nektary (Kontzevich).

Fr. Seraphim’s deepest conviction, which he tried to instill in all of his spiritual children, was that, “Pain of heart is the condition for spiritual growth and the manifestation of God’s power. Healings, etc., occur to those in desperation, hearts pained but still trusting and hoping in God’s help. This is when God acts. The absence of miracles today (almost) indicates this lack of pain of heart in man and even most Orthodox Christians — bound up with the ‘growing cold’ of hearts in the last times.” (799) This was often intended as a reminder of the importance of humility to people going through difficult times, but it could also serve as a warning to overzealous converts: “Be aware…everything you need to deepen your faith will come with suffering — if you accept it with humility and submission to God’s will. It is not too difficult to become ‘exalted’ by the richness and depth of our Orthodox Faith; but to temper this exaltation with humility and sobriety…is not an easy thing. In so many of our Orthodox people today (especially converts) one can see a frightful thing: much talk about the exalted truths and experiences of true Orthodoxy, but mixed with pride and a sense of one’s own importance for being ‘in’ on something which most people don’t see…” (802)

As his pastoral concerns (and his immense correspondence) grew, his thought and writing began to focus on what he called “Orthodoxy of the heart,” the last and best philosophical idea that his mind produced over the course of his life. Fr. Seraphim taught that Orthodoxy was “something first of all of the heart, not just the mind, something living and warm, not abstract and cold, something that is learned and practiced in life, not just in school.” (830) This idea in no way replaced his earlier preoccupations, set forth in Orthodoxy and the Religion of the Future, but organically emerged from them: “The antichrist must be understood as a spiritual phenomenon. Why will everyone in the world want to bow down to him? Obviously, it is because there is something in him which responds to something in us — that something being a lack of Christ in us. If we will bow down to him (God forbid that we do so!), it will be because we feel an attraction to some kind of external thing, which may even look like Christianity, since ‘antichrist’ means the one who is ‘in place of Christ’ or looks like Christ.” (833)

Fr. Seraphim addressing Orthodox seminarians in 1979

(Damascene, 865-866)

Fr. Alexey Young recalled, “One of the most striking aspects of Fr. Seraphim’s guidance was, first of all, his utter disinterest in controlling me or anyone else. Unlike some others, he did not play guru or give orders (he had spiritual children, not disciples). I asked for his opinion and he gave it — frankly — but always he left the final decision up to me. This meant that I was bound to make mistakes, but he knew that I would learn from the consequences of those mistakes. Also, whenever he felt the need to criticize something, he always balanced it with something positive, so that one did not feel somehow destroyed or discouraged about one’s work. This is an indication of spiritual health as opposed to the cult-like behavior of those who always think they know better.” (815)

There were even children in the monastery at various times — some of them came from families of longtime friends and supporters and were simply visiting, but others had been all but orphaned. Fr. Damascene describes one such child, “a very troubled boy, one who had been deeply wounded by life. He had never known his African-American father, and had been made to feel that something was wrong with him because he was the only black person in his family. His upbringing by his unstable, white mother had been dreary and oppressive — which was the real reason why he wanted to come to the hermitage.” (565) Truly, many are the labors of a hieromonk: one of Fr. Seraphim’s foremost concerns was now, of all things, parenting. Thinking about how to educate Orthodox children in a way that would keep them in the faith, he actually found himself coming back to classical secular culture, the literature and music (Bach and Handel) from which he had deliberately turned away as a young convert. Now, however, he would say, “Everything in Dickens…is full of Christianity. He doesn’t mention Christ even, but it is full of love. In The Pickwick Papers, for example, the hero Mr. Pickwick is a person who refuses to give up his innocence in trusting people… In fact, these nineteenth-century novels…are very down-to-earth and real; and they show how to live a normal Christian life, how to deal with these various passions that arise. They do not give it on a spiritual level, but by showing it in life, and by having a basic Christian understanding of life, they are very beneficial.” (975) Eventually there were sufficiently many children and young people visiting Platina that Fr. Seraphim could design and teach an entire summer course on literature and philosophy, not only Christian but including, for example, Homer and Plato.

In his final years, Fr. Seraphim’s eschatological premonitions were accompanied by a deep sorrow, grief for a “normal” world which he knew was never going to return. Three weeks before his death, he listed the following signs of the coming apocalypse to a gathering of pilgrims:

(Damascene, 1014)

In the late 2010s, all of these points are much more topical than they were in 1982. Of course, Fr. Seraphim would not be Fr. Seraphim if he had not also added to that list, “The truly weird response to the new movie everyone in America is talking about and seeing: E.T., which has caused literally millions of seemingly normal people to express their affection and love for the hero, a ‘saviour’ from outer space who is quite obviously a demon — an obvious preparation for the worship of the coming antichrist.” What can I say, the man just did not like the films of Steven Spielberg.

In 1981, Fr. Seraphim was invited to speak at the University of California, Santa Cruz before a student organization that had the goal of studying various religions. His talk, which was eventually published by St. Herman Press as a short pamphlet titled God’s Revelation to the Human Heart, was addressed to an audience which was very familiar and had extensive personal experience with various spiritual trends and teachings, but which had mostly never heard of Orthodox Christianity. It is practically impossible to know what to say in such a setting; Fr. Seraphim told them a little bit about Lives of Saints, a little bit about St. John, and a little bit about religious dissidents in the Soviet Union that, in his opinion, exemplified enlightenment earned through suffering. These disparate elements perhaps did not fit perfectly together, but they allowed him to recapitulate his credo in two parts. First: “How can a religious seeker avoid the traps and deceptions which he encounters in his search? There is only one answer to this question: a person must be in the religious search not for the sake of religious experiences, which can deceive, but for the sake of Truth. Anyone who studies religion seriously comes up against this question: it is a question literally of life and death.” And, second:

(from God’s Revelation)

Among the students in the audience was one John Christensen, the future Fr. Damascene.

Fr. Seraphim died very suddenly and very painfully. After several days of intense stomach pain, he agreed to be brought to a hospital, where “the doctors found his condition to be very serious. His blood had somehow clotted on the way to his intestines, and part of the intestines had already died and become gangrenous. This occurrence, the doctors said, is very rare, and when it appears much damage is usually done before one knows what is happening.” From the beginning it was hopeless: “The doctors…were coming across a great dilemma: if they used anticoagulants to prevent the blood from clotting, he would bleed to death internally, but if they did not use such drugs more and more tissue would die. A specialist in this rare disease was called in from San Francisco, but even he was at a loss to stop the damage. At this point the doctors could give Fr. Seraphim only a two percent chance of recovery.” (Damascene, 1019-1020) He fell into a coma and died several days later, on September 2nd, 1982 (August 20th by the Julian calendar).

This was very traumatic for the Platina community; its members gathered in the hospital and prayed day and night for him to be healed, but their request was not granted. Unlike the legendary saints in medieval tracts, the man whom they saw as their spiritual teacher was not able to share any deathbed wisdom or final heavenly vision with them — Fr. Herman reported seeing him in delirium after surgery, “tossing and turning in unbearable agony, cursing people who were the closest in the world to him, saying he hated everyone, and threatening to get revenge once he got free.” (1019) Later, they came and sang hymns to him, but he was no longer able to speak.

Bishop Nektary (Kontzevich), an elderly hierarch who still remembered the great Russian monasteries from his boyhood, who had been an ardent supporter of St. John, who had known Eugene Rose from San Francisco, and who had ordained Fr. Seraphim to the priesthood, attended Fr. Seraphim’s funeral and gave a sermon on the fortieth day after his death. Fr. Seraphim had wanted to focus on English-language missionary work, aimed at Americans — he never questioned or fought with the ROCOR hierarchy, but as we have seen, in certain ways he had distanced himself from the Russian Orthodox community — and yet, perhaps Bishop Nektary perceived that his life somehow had more importance for Russia. At any rate, he confidently said, “Fr. Seraphim was a righteous man, possibly a saint,” (1036) thus marking the moment at which the idea of Fr. Seraphim came into existence.

Things fell apart very quickly after Fr. Seraphim’s death.

Fr. Herman continued on as the head (hegumen or abbot) of the Platina monastery. He had already held this office previously, as Fr. Seraphim did not want to be seen as an authority figure. But now he was not only in charge of the monastery, he also had “ownership” of Fr. Seraphim’s reputation — he could position himself as the preeminent living link to Fr. Seraphim. Very soon, Fr. Herman got into severe conflicts with Platina’s ruling bishop (Archbishop Anthony of San Francisco, St. John’s successor in this office) over issues of obedience. At the same time, word began to spread about sexual misconduct by Fr. Herman, leading to his suspension by ROCOR (pending investigation into his conduct) just two years later, in 1984. Due to his obstructionist stance, and his refusal to give up the office of abbot, he was defrocked by ROCOR altogether in 1988. Thereafter, he left ROCOR and took the entire monastery with him, and for the next 12 years, the St. Herman of Alaska Brotherhood was lost in the wilderness, as a “vagabond” Orthodox community with no link to any canonical Orthodox Church. Fr. Herman veered left and right, aligning himself first with other rogue Orthodox groups, then with New Agey pseudo-Christian cults (one of these, the so-called “Holy Order of MANS,” briefly proclaimed Fr. Herman as their spiritual leader), some of whose members were similarly alleged to have committed sexual abuse. When added to Fr. Herman’s own autocratic tendencies, these influences made the Platina community overtly cult-like; while continuing to profess “Orthodoxy,” Fr. Herman and his new associates began to exercise greater and closer control over the lives of their followers, and by this time many key figures from the Brotherhood’s history — people such as Fr. Alexey Young who had known Fr. Seraphim in person — had simply left. It was not until 2000 that whoever was still remaining had managed to “persuade” Fr. Herman to step down from his office, thus finally reversing direction. The Platina monastery subsequently sought reconciliation with canonical Orthodoxy and joined the Serbian Orthodox Church, under whose jurisdiction it continues today. (If any of this had any theological meaning, perhaps it is that now, the other great suffering Orthodox Church shares in Fr. Seraphim’s legacy.) Fr. Damascene (Christensen) serves as abbot, as of this writing.

In the 2000s, a small group of people, who had previously spent time at the monastery while Fr. Herman was in charge of it, started a short-lived Internet community on Livejournal with the heartbreaking title, “St. Herman’s Orphans.” Some of these people had been confused spiritual seekers, not unlike those described in Orthodoxy and the Religion of the Future, wandering through the wasteland of religious experimentation before drifting into Platina. There were also many other reasons for coming; one of them candidly wrote, “My family was and is screwed up.” But, whatever anyone’s original motivation might have been, the overall tone of this community was one of total exhaustion; many of its members felt that they had completely burned out on Orthodoxy, and in many cases on all of Christianity and even any other kind of religious belief. One wrote, “I have a difficult time seeing things in a spiritual dimension. The glass of water I’m drinking now is more real to me than God.”

Metropolitan Hilarion (Alfeyev), The Spiritual World of Isaac the Syrian

Here is a somewhat more positive take (from Livejournal user ‘padraigc8’), though the outcome is more or less the same: “I visited the USA back in ’94 and spent four weeks or so visiting St Herman’s Monastery, St. Paisius Abbey, Raphael House, St. Xenia’s Skete, Theophany Skete in Chico and a few other places…spent years before this reading St Herman’s Press books, got caught up in it quite a bit…loved the spirit of it all…especially DTW zine…I ain’t no Youth of the Apocalypse, I’m old…and my heart was seared by the pain and authenticity of the struggle of so many of the folks I met over there…I came back home spent the next 10 years serving the church and then all burned out and tired; went, as we say in Oz, ‘walkabout’… [Spelling and punctuation cleaned up a bit. -FL]”

(“DTW zine” refers to a magazine called Death to the World, which some young Platina-affiliated zealots published in an effort to communicate with the punk and metal “scenes,” to which they themselves had previously belonged. One of the founders, LJ user ‘metalgypsy’, wrote, “My heart was moved enough by Orthodoxy that, at age 19, I left punk on the streets, to become an Orthodox nun in the brotherhood.” She spent 10 years as a nun, but ultimately left. The magazine is still being published by someone else, with Fr. Damascene’s blessing.)

As the following shows, Fr. Herman had a great deal to do with this defeated feeling:

(from LJ user ‘monksrock’)

Some community members had more positive feelings about Fr. Herman (evidently they did not have personal experience of such advances), seeing him as a mentor whom they hyperbolically described as having “led hundreds, if not thousands of people to faith,” but ultimately they also had to concede, “Fr. Herman’s hard fall from grace is not in any way justified by his many good works… No one is justified by their works and all fall and have fallen short of the grace of God. The fact is, the taller the mountain, the more earth shaking the fall. It is not a surprise that many have abandoned him and that many, many people cannot forgive him.” On a different website, another former follower of Fr. Herman, who retained a similarly high opinion of him, wrote, “I know some of you who read this post may think I am unaware of the sin that my spiritual father fell into late in this life. I am aware, mourn his fall, and wish for God’s healing on all affected by it.”

Icon of the Ladder to Paradise. Byzantine Empire, 12th century.

Icon of the Ladder to Paradise. Byzantine Empire, 12th century.

It stands out that none of these people, no matter how bitter or disillusioned, has ever attributed any such incident to Fr. Seraphim. Rather, the general consensus is that Fr. Seraphim’s presence was the only serious check on Fr. Herman’s urges, and that this ugly situation developed after Fr. Seraphim’s death. However, it also seems that a distance had begun to appear between them close to the end of Fr. Seraphim’s life; in an article written many years later, Fr. Alexey Young stated, “Fr. Herman himself told me that the very last words spoken to him by Fr. Seraphim were: ‘I’m finished with you. Damn you!’ Fr. Seraphim’s uncharacteristically angry words bespeak a mind deeply troubled over Fr. Herman’s general behavior and suggest that there was more going on than any of us suspected at the time.”

St. Isaac of Syria

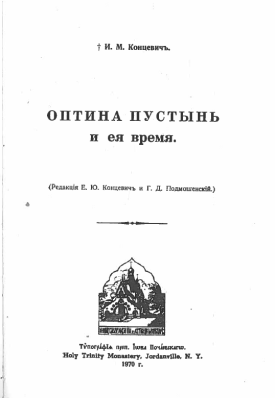

There was a time when the young Gleb Podmoshensky had sincerely tried to uphold the Orthodox faith and the Russian tradition. As a young man, he worked with the Russian emigrant intellectual Helen Kontzevich to edit her late husband Ivan’s extensive notes on the history of the renowned Optina Monastery in Russia. This book was eventually published by a ROCOR press under the title Optina Monastery and Its Time, listing Ivan Kontzevich as the author, but giving editorial credit to both Helen Kontzevich and Podmoshensky. It contains a wealth of historical and theological material that otherwise might have been lost entirely, and has sustained multiple editions in Russia even recently.

Optina Monastery and Its Time, title page of first edition.

Optina Monastery and Its Time, title page of first edition.

“Edited by H.Yu. Kontzevich and G.D. Podmoshensky.”

But, the same ebullient, imaginative Gleb, who is the source of so many lively passages in Fr. Damascene’s book, and who did, after all, willingly follow Eugene Rose into the California wilderness to suffer many hardships, and who was even injured by their archaic printing press — the inevitable conclusion is that this same man eventually betrayed his Church, his holy office, his followers, his closest friend, and finally himself. Ironically, in Eugene and Gleb’s joint Russian-American enterprise, it was the Russian side that turned out to be fatally unfit.

St. Symeon, the New Theologian, Homily 66

Fr. Herman (Podmoshensky) died in 2014, at the age of eighty. A leading ROC website published an obituary that mostly glossed over his misdeeds (which, however, are very widely known at least within ROCOR), and mentioned that he “had suffered for at least a decade from Parkinson’s disease and diabetes, and had noticeably weakened within the past several years.” He died in Minneapolis, far away from Platina; in various other sources, it was implied that he had been living there alone for some time.

Fr. Damascene’s book does not discuss any of this — only at the very end, in the author’s note, does he mention “the untenable ecclesiastical status that the St. Herman Brotherhood entered into after Fr. Seraphim’s repose: a status which, thanks be to God, has been rectified since the earlier version was published.” (1065) He is referring here to an earlier edition of Father Seraphim Rose: His Life And Works, which appeared in 1993 (under the title Not Of This World: The Life and Teaching of Fr. Seraphim Rose), when the monastery was still in its schismatic period. This first version of the book was heavily “supervised” by Fr. Herman and may have had large parts written or dictated by him; at the time, Fr. Alexey Young wrote a very critical article about the “self-serving one-sidedness” of these segments. (Perhaps for this reason, Fr. Alexey was asked to review the current edition and had a much more positive opinion.)

Of course, all of this questionable material has been removed from the current edition, but one could ask if Fr. Damascene really did the right thing by omitting any mention of what happened to the monastery in the 1990s. Undoubtedly he would argue that the book’s primary focus should be on Fr. Seraphim’s life, and that anyone who really wants to know about Fr. Herman would have no trouble finding the information somewhere else (as I have done). I won’t try to debate that view — I agree with it — but still, a large part of what we learn about Fr. Seraphim in this book, things that he allegedly said or thought, actually comes second-hand through Fr. Herman’s reminiscences and stories, and at some point one has to wonder how much of this can be trusted. For instance, early on, Fr. Damascene’s story of how Eugene and Gleb started the Brotherhood culminates with Eugene allegedly telling Gleb, “I trust you!” (265) — but even this is quoted from Fr. Herman…

Fr. Seraphim in 1976 (Damascene, 673)

But let us now leave Fr. Herman, who in any case now has to answer to God on his own, and let us return to those people who had been at Platina when it was under his “leadership.” Among them, there are also many who do not refer to any specific negative incident or experience — quite the opposite, they even managed to keep many happy memories — and yet, somehow, they came to a point where they felt unable to continue in Orthodoxy: “Eventually, I moved to California and for one year I owned an Orthodox Bookstore in Berkeley, California with the help of the monks and nuns from Forestville and Platina…Father Innocent built and painted a beautiful iconostasis. Eventually, I could not afford to keep the bookstore open and I had to close it. I have gone in and out of trying to be a good Orthodox person. When everything fell apart, I was living in California but did not belong to any parish so I was left out in the cold basically and really felt orphaned.” It is noteworthy that very few people express outright regret that they had ever come across the monastery in the first place. Even among those who feel betrayed by Fr. Herman or resentful toward Orthodoxy, there is often a kind of lingering sadness over having discovered something unimaginably beautiful, only to lose it forever — through the failings of Fr. Herman or other community members, but also, perhaps, through some other subtle crisis of faith.

(from LJ user ‘jafnhar’)

This person went on to comment: “Orthodoxy…has difficulty updating itself and concurrently maintaining its appeal. I don’t know if what Fr. Seraphim did entailed ‘crucifying his mind’ or just ignoring what he didn’t want to hear, or if that was the same thing to him, and if it came with ease or difficulty. What he did, however, is nihilistic in a very real way.” Overall, this person now self-identified as an atheist, but mentioned that he or she still attended services at the local Orthodox parish occasionally.

(from LJ user ‘createdestiny’)

However, this latter person also writes, “I wonder if I’ll live to see [Fr. Seraphim] canonized? I have good memories of celebrating his repose at the monastery in the days when the Brotherhood was seen as ‘uncanonical.’ There would only be about 20 people there for Liturgy at his grave. I hope he remembers us before God…” In another place, he or she comments, “Sometimes I suspect that Christ’s yoke is light and the yoke I bear is the yoke of my own fears.”

Unfortunately, these problems cannot be solved by simply looking up some relevant quote from the Holy Fathers — for one thing, anyone who ever stayed at Platina has already heard enough such quotes to be able to dismiss them out of hand if so inclined. But at the same time, these are feelings with which any serious Orthodox believer is very familiar:

“I believe.”

“Because it is said that if you have faith and order a mountain to move, it will move…well, nonsense. But still I am curious to ask: would you move the mountain or not?”

“If God commands, I will,” Tikhon answered quietly and reticently, again beginning to lower his eyes.

“Well, that’s the same as if God were to move it Himself. No, I mean you, as a reward for your faith in God?”

“Perhaps I won’t.”

“‘Perhaps’? Not bad. Why do you doubt it?”

“My faith is imperfect.”

“What? Your faith is not perfect? Not entirely?”

“Yes…perhaps, not to perfection.”

[…]

Tikhon again smiled at him. “On the contrary, total atheism is more respectable than secular indifference,” he added with joyful simplicity.

“Oh! Is that so?”

“A perfect atheist stands upon the penultimate step leading to the most perfect faith (then he will either rise above it, or not), but one who is indifferent has no faith at all, only foul fear.”

Fyodor Dostoevsky, “At Tikhon’s”

Orthodoxy, in general, has many “orphans.” At one point, Fr. Seraphim wrote an outline listing “what he called ‘obstacles in the Orthodox mission today,'” of which one was “Discouragement, giving up — ‘quenched’ syndrome.” (Damascene, 847-848) Every parish priest has seen (or even personally experienced) this — one is first awed by Orthodox tradition, philosophy, aesthetics and so forth, then joins the Church and, after a period of elation in which everything seems to fall into place on its own and the required repentance seems to come very easily, suddenly finds that Orthodoxy has become difficult in a way that no longer seems to provide any reward, and then starts to resent it for not “updating itself.” Or, in a much more extreme example, “in San Francisco, a few blocks from one of our Russian Orthodox churches…is a house painted black; inside is a temple of satan. Recently some sociology professors and students of the University of California at Berkeley made a study of the regular members of this ‘temple.’ They found that one of the largest groups of people who belonged were sons and daughters of Russian Orthodox parents; and their theory is that Russian Orthodox children, if they are not fully aware of their own Faith, are easier than others to convert to satanism, because their religion is so demanding, and if they don’t fulfill its demands their souls feel an emptiness.” (Damascene, 862) Indeed, the immense religious revival in Russia during the 1990s was accompanied by a parallel explosion of unhinged occultism, and the latter nullified much of the good that the former had brought about…

The Shepherd of Hermas

Unknown author, 2nd century

If Fr. Seraphim could return to our world, for a short time, what would he say to the disillusioned Orthodox converts from Platina, for whom he surely feels some responsibility in heaven? Perhaps his answer would have been to just tell them what he always said before: “‘Suffering,’ Fr. Seraphim stated, ‘is the reality of the human condition and the beginning of true spiritual life… The right approach…is found in the heart which tries to humble itself and simply knows that it is suffering, and that there somehow exists a higher truth which can not only help this suffering, but can bring it into a totally different dimension.’” (Damascene, 475) All Orthodox Fathers know and teach that the positive feelings of improving one’s life, admiring Church art, studying the Scriptures and so on, while undoubtedly a good and worthy part of religious life, are nonetheless not the same thing as true religious faith, which, like sainthood, is ultimately impossible to define, but which certainly is not an accessory that can be “updated.” But it is difficult to say this in a meaningful way to people who certainly appear to have done more than their share of suffering, and yet for whom the awaited and sincerely labored-for enlightenment and consolation never came. All one can say is that these same people may have overstated Fr. Seraphim’s supposed monolithic “completeness” — what if all of their pain, doubt, and disappointment had been intimately familiar to him all along, because these things were inseparable companions of his own faith all those years?

(Conclusion: part 9.)

Thank you so much for this excellent series of articles on Rose and his work. You demonstrate not merely a familiarity with his life and work, but a true understanding of his spirit, his mind, his motivation and his import. You respectfully pointed out some of his blind-spots or shortcomings, but more importantly and more extensively, you captured and described what made this man, yes, a genius and an authentic inheritor and transmitter of the deepest spirit of the Holy Fathers and Orthodoxy. God bless you.

Your article on Isaac of Nineveh is also excellent.

LikeLike

God saves! Thank you for reading.

LikeLike