“Everything hurts in the tree of human life.” (Leontiev, 189)

“Everything hurts in the tree of human life.” (Leontiev, 189)

I meant to write about Rozanov. I couldn’t quite find the right starting point. But, in my reading, I kept returning to one of his friends and early influences, Konstantin Leontiev. Then the path became clear, even with a connection to the feast day (a merry Christmas to all readers, whoever they may be).

Leontiev (1831-1891), to the extent that he is known at all, is generally classified as a right-wing philosopher who professed monarchism and Orthodox traditionalism. But that is also a common description of Rozanov, who was a far more multifaceted phenomenon in reality. Leontiev’s career as a writer of philosophical texts began only around age 40. His life before then was quite colorful: born into a declining provincial noble family, he was at various times a medical student, a military volunteer, an unsuccessful novelist (who, nonetheless, published several works, all of them totally unknown now and, for the most part, in his time as well), a professional doctor, and a diplomat serving Imperial Russia in the Ottoman Empire. Later in life, he worked as a journalist and then an official censor, the latter position leading to one amusing anecdote where he edited a poem containing the line “even generals take bribes” to read “even liberals take bribes.” Shortly before his death, he became an Orthodox monk, completing a religious journey that had begun in the early 1870s. At the very least, it was a life full of rich, diverse experience.

When you first hear about a “thinker,” the first impulse is usually to look for some brief summary of his thought, ideally in the form of a single representative work. With Leontiev this becomes the first difficulty, since he never articulated a clean summation of his philosophy. For much of his life, his written output was focused on novels, some published, some unfinished, and some destroyed. “Eight years later, in a letter to Vsevolod Sergeyevich Soloviev, [Leontiev] expressed more openly that he had burned his novels partly ‘out of pride,’ partly ‘out of melancholy.’ ‘Out of pride’ — because he believed himself to be capable of creating completely new literary forms, which would have put an end to Gogol’s influence on Russian letters. ‘Out of melancholy’ — because he had planned to publish the entire work all at once, ‘to amaze everyone,’ and in the meantime was working on ‘little porcelain teacups’ — ‘Pembe,’ ‘Chriso’ and other stories, hoping that they might be noticed by critics. But years passed, ‘and nobody said a word.’ ‘This silence did not humble me and only intensified my pride, my self-conceit, although it did gradually submerge me in incurable sadness,’ Leontiev admitted.” (Volkogonova, 226-227) Even long after he had given up on fiction entirely, its apparent rejection by the reading public still bothered him. As late as 1891, he wrote to Rozanov, “Thank you for your good intentions, but one hardly has to be ‘ill-informed’ to have never heard of me. You are not the first to ‘discover’ me like [Columbus discovered] America, despite the fact that I have been working seriously as a publicist since 1873… Why is that? I don’t know… Many of those who sympathized with me tried to explain it one way or another, but in my opinion, the explanation is…very simple: others wrote little about me; there was little criticism and little praise; few attacks and few expressions of sympathy; i.e., there were few serious critical opinions in general[.]” (Rozanov, XIII/332)

Indeed, Leontiev published his first essay in 1868. His writing over the next 10-15 years was collected in a volume titled Byzantism and Slavdom, later expanded and republished in 1885-1886 as The East, Russia, and Slavdom. This is the only one of his works that can still claim anything other than a purely academic audience, and also the one that attracted the most attention (relatively speaking) during Leontiev’s lifetime — the title essay “Byzantism and Slavdom” made a strong impression on Rozanov, to the extent that he was moved to seek out and write to the author. So, if there ever was such a thing as an exposition of Leontiev’s beliefs, one might expect to find it here.

Page numbers from this 2007 edition by Eksmo.

Page numbers from this 2007 edition by Eksmo.

But, if so, one will be disappointed. The East contains some philosophical thinking, but it is scattered between more journalistic articles (Leontiev was, briefly, a correspondent for a minor newspaper in Warsaw), essays focused on political analysis, a few reactions to current events (like a speech given by Dostoyevsky), and even fewer impressionistic personal anecdotes. Curiously, even after Orthodox Christianity had become the central focus of his life, Leontiev continued to write abstractly about such topics as nationalism or the risks posed by technology, but wrote very little about religion specifically. The final text included in the 2007 edition is called, “My conversion and life on Holy Mt. Athos,” but neither is actually treated in this brief autobiographical essay; it seems never to have been finished, breaking off after a few childhood impressions, which, as the author admits, were not particularly religious.

Reconstructing a coherent worldview from this eclectic collection is not the most straightforward task, nor the most important. Nonetheless, I will give a brief sketch.

The single most prominent (and, unfortunately, most dated) topic in The East is the question of pan-Slavism and Russia’s relations with the Orthodox peoples of the former Ottoman Empire. Leontiev’s thoughts are heavily informed by personal experience and the years he spent in Turkey as a diplomat. His opinions, however, are quite unlike what one might expect from an infamous 19th-century reactionary. He is consistently skeptical of pan-Slavism as a grand unifying project. In fact, he sees no meaning in the concept at all:

(Leontiev, 152-153)

From the vantage point of the 21st century, Leontiev is simultaneously absolutely clear-sighted but also not entirely correct. In certain subtle ways, the influence of pre-revolutionary Russian culture on Serbian culture reached its peak after 1917, when a large number of Russian refugees (including St. John of Shanghai) temporarily settled in Belgrade. Perhaps that is why, to this day, these two cultures still see reflections of themselves in each other, more than in Leontiev’s time — having never lived in Serbia himself, he viewed it as peripheral to Greece and Turkey and rarely mentioned it.

But, as a political project, of course pan-Slavism was stillborn and never drew a single breath. Leontiev sees South Slavic culture as being under-developed, but really he readily applies the same criticism to Russian culture: “Has it been decided what Russia must undergo in the future? Is there any positive proof that we are young? Some find that our relative intellectual barrenness in the past may serve as proof of our immaturity or youth. But is that so? A thousand-year poverty of creative spirit is hardly a guarantee of bountiful fruits in the future.” (Leontiev, 229) The objective veracity of these statements is not really relevant, but one does see that Leontiev’s views of Russia’s history and future were no less skeptical than his assessment of pan-Slavism.

So far, these are narrowly political matters that appear quite obsolete now, especially to an English-speaking audience. But contemplating pan-Slavism leads Leontiev to a more general philosophical critique of political nationalism. This is a delicate matter, in part because there is already a certain expected template for how a religious conservative might take this position (for example, the argument that faith supersedes ethnicity, “There is neither Jew nor Greek, there is neither bond nor free, there is neither male nor female: for ye are all one in Christ Jesus“), and, therefore, also an expected template for refuting it. To some degree, this “standard” perspective is present in Leontiev’s writing; for example, he castigates the Bulgarian political elite for bringing about the separation of the Bulgarian Orthodox Church from the Patriarchate of Constantinople, and sees this as a fatal flaw in the entire project of Bulgarian independence. The absolute political dependence of the Ecumenical Patriarch in our day is proof enough that Leontiev was wrong on that point. But, in its fullness, Leontiev’s analysis goes far deeper than this. In an essay with the provocative title “National politics as an implement of global revolution,” he wrote:

(Leontiev, 729-730)

“Ruins of an ancient city,” John Martin, 1810.

Again, we have to separate this passage from its 19th-century political and ideological particulars (alleged Greek indifferentism, Leontiev’s insistence on explicit social separation of the estates) in order to see the real thought in it. The thought is that the success of political nationalism is often followed, counter-intuitively, by cultural self-erasure, setting up the denatured nations for an inevitable “cosmopolitan” unification further down the line. In Leontiev’s words, “The principle of political nationalism, brought into life sometimes by force of arms and other times by transformation of institutions, in practice turns out be merely a new and powerful means of cosmopolitan, i.e., anti-national democratization of Europe… All are the same, all alike, all related…” (435) He writes about the unification of Italy, another success story of 19th-century nationalism:

(Leontiev, 734-735)

Leontiev’s other examples include Germany, which “not only became more internally homogeneous than before, but also came to resemble its vanquished enemy France in its internal order,” (739) and Russia itself, whose failure in the Crimean War led to “cosmopolitan” reforms and, ironically, renewed success in world affairs. There are also other examples along these lines — conflicts that appear to be purely national in character, but ultimately blur the boundaries between the winner and the loser. Essentially, “nationalism” as a contemporary political ideology comes into conflict with “nationalism” as an expression of the nation’s cultural distinctiveness.

(Leontiev, 771-772)

Fr. Seraphim (Rose) once asked an audience of seminary students, “Who are you? What is your identity?” What he meant, perhaps, was that the seminarians had some sense of what they were not (they were not Catholic, Protestant, liberal, etc.), but their understanding of what they were was limited to certain distinguishing outward characteristics — form rather than content. And this question need not be about religious identity; it is one that each of us should contemplate without immediately reaching for some obvious, glib, standard explanation. For many (perhaps not all, but many) nations, the “national project,” worded in 21st-century language, boils down to, “secede from somewhere and then hand the keys over to the EU.” What Leontiev objects to is not the secession, but the handing; not the reclamation of sovereignty, but the surrender of it; but he observes that, without a sufficient cultural foundation, one has the other as its inevitable consequence. Political separatism turns into political unification at the next bend of the spiral, and that kind of unification does demonstrably lead to homogenization and the loss of identity. In the late 20th century, the European nations were just as Leontiev describes 19th-century Italy: “fragmented and dependent,” but still capable of significant cultural creation. To give one example, the creative peak of cinema as an art form had a clear national character, with French, German, Italian, Polish and other shades. Post-2000, unified Europe produced nothing. At first it seemed like this would be compensated by an improvement in the standard of living; now, the mere notion sounds laughable.

“Landscape with an imaginary view of Tivoli,” Claude Lorrain, 1642.

Earlier, I wrote about Mishima’s Runaway Horses. On the surface, this was his most overtly nationalist work, glorifying a young patriot who is willing (and eager) to sacrifice his life for his ideals. But the book contains hidden layers that are, at best, highly ambivalent toward political nationalism. Isao Iinuma would have had no trouble answering Fr. Seraphim’s question in his own way — he certainly knew who he was. In Leontiev’s classification, Isao would be a staunch defender of “cultural nationalism,” railing against exactly the kind of faceless financial elites that Leontiev would have despised. But…Isao’s understanding of the culture that he means to protect is based on a strange pamphlet by an unknown, likely pseudonymous, possibly nonexistent author. The financiers whom he hated were implements of the Emperor, who later would have disappointed Isao (had he lived long enough to see it) by renouncing his divinity, and who, 20 years after that, was still nominally head of the country that Mishima dismissively called “an inorganic, empty, neutral, drab, wealthy, scheming, economic giant in a corner of the Far East.”

Mishima would have understood Leontiev’s idea intuitively, even if he would have skimmed over the details. In a way, Spring Snow and Runaway Horses refute Leontiev’s preoccupation with the aristocracy as a “higher” class. The aristocracy did just as much to bring about the “democratization” that horrified Leontiev as anyone else, because, if political nationalism can be used to dismantle nationalism, then political democratization can just as well be used to dismantle democracy. Yet, nonetheless, Leontiev may have preemptively identified the shape of the explanation that resolves Mishima’s passionate defense of Japanese culture with the overtly parodic character of his political activities.

The problem posed by Leontiev, and faced by any “cultural nationalist,” cannot be solved with glib political prescriptions. Leontiev himself emphasized that simply attempting to defend traditional values is hopeless. His pessimistic view of Italy is rooted, not so much in its perceived abandonment of its old values, but in the lack of any “new creativity” to take their place. In fact, Leontiev is not a “conservative” in the sense of seeking to preserve some old way of life. Everywhere in his writing, he emphasizes the impossibility of doing so, because the “stones” left over from past centuries are always, in his opinion, inferior to “the expressiveness of life.” Lose the latter, and there is no point in saving the former; so, the foremost task of cultural nationalism is not to conserve, but to create. Perhaps this is what causes the inherent contradiction with nationalism as a political movement, because in politics any and all creativity is always subordinate to the political goals of the moment. (Part of the tragedy of Runaway Horses is that nobody needs Isao to create anything — that is not part of the script.) Creation is a conscious, individual act, and therefore cannot happen on a schedule or by directive.

Leontiev himself was not able to offer any solution to this problem. Unfortunately, in “Byzantism and Slavdom,” where he pointed out that “Slavdom” is a word without meaning, his intended counterpoint of “Byzantism” really does not have any specific meaning either. The essay begins with, “What is Byzantism? Byzantism is first and foremost a certain kind of education or culture, which has its own distinguishing characteristics, its common, clear, striking origins and its well-defined historical consequences.” (Leontiev, 127) This, of course, is a non-answer, and Leontiev is not really able to elucidate upon it, though his historical references indicate sufficient knowledge of Byzantine history. The only specific “distinguishing characteristics” that he presents are caesarism (absolute monarchy), and Orthodox Christianity as a civilizational principle. These are also the only two guiding lights he can think of for how to actually accomplish the task of cultural creation. But monarchy (or, more broadly, aristocracy) ultimately failed to do it (again, Runaway Horses shows how), and in any case it is gone now. As for Orthodoxy, it is my sincere belief that Orthodox spirituality is incompatible with organized politics. That does not mean that political parties cannot or should not invoke Christian values when building their platforms, especially if it helps in any way to keep them within some semblance of moral boundaries. But the Church will cease to be a living organism if it becomes a political organization. It does not even work for purely religious goals. From time to time, there is discussion in Orthodox circles about whether “more should be done” with regard to missionary and social work. These conversations rarely go anywhere, and when such efforts succeed, it always happens on the level of an individual parish or clergyman. Every conversion has an individual character, a unique meeting with God; every believer experiences the Liturgy individually. Even contact with the Church is often made through individuals — the writings of St. Isaac of Syria (whom Leontiev also cites), the lives of Fr. Seraphim or St. John of Shanghai, even just conversation with a parish priest. Leontiev wrote, “The sincerity of individual faith is highly contagious…I, too, was greatly influenced by others who had this sincerity.” (882) Perhaps this is simply how God has willed it.

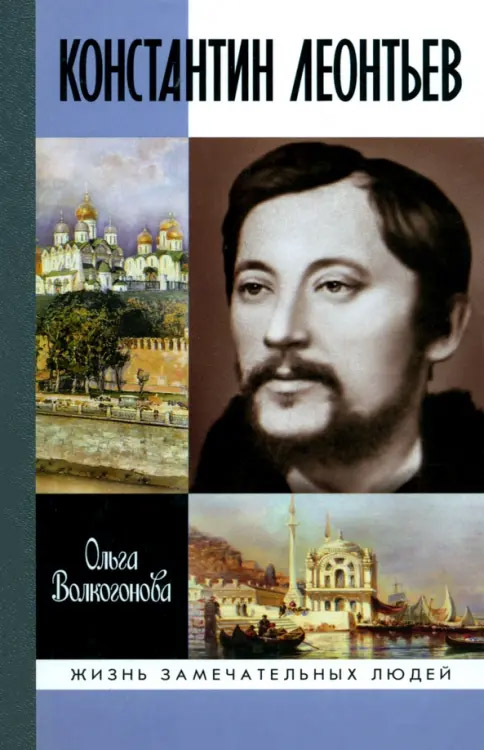

And so Leontiev never became a nationalist icon or a major philosophical influence. Leontiev’s biographer writes, “Konstantin Nikolayevich still remained, despite his extraordinary person, a ‘supporting character’ in the history of Russian thought. ‘Oh, ungrateful posterity!‘ — so Bunin will write regarding Leontiev and his writings, finding some of them to be ‘literally on the level of Tolstoy’s pieces.’” (Volkogonova, 441) This is an exaggeration, but somehow Leontiev tends to attract vacuous extremes instead of serious analysis. My copy of The East is prefaced by an utterly ridiculous essay by Berdyayev, full of bizarre, ranting statements such as “Leontiev passionately loved wearing the mask of cruelty and supermorality” (7) and “[he] found himself in a place unbearably foul-smelling, in which there is nothing creative or original and beauty is desecrated at every step,” (9) with fragments from Leontiev quoted out of context, and with no argumentation whatsoever. Unfortunately, this is about the extent of Leontiev’s influence. Perhaps not without reason: argumentation was not his strong suit either. As Volkogonova writes, his “geopolitical schemes look quite modern, but they had one weakness, which, perhaps, impeded their dissemination — they were supported by nothing except the author’s intuition. Where he presents arguments, they are usually aesthetic, or, less frequently, theological. Both work only within Leontiev’s own coordinate system and are unlikely to convince any opponent. Indeed, they never did — Leontiev’s name still remained unknown to a wide circle of readers.” (372-373) One has to do his work for him, extracting pieces of his thought from disconnected essays and attempting to assemble them into some more or less coherent picture. As a philosopher, he mainly succeeds in provoking the reader, who might be expecting something a little more in line with the mainstream of 19th-century conservative thinking. Yet his thoughts on the fate of nations, while outdated in some aspects, are surprisingly contemporary and disquieting in others, and should not be ignored.

But there is a different side of him, which is totally invisible in The East, and utterly striking in his biography (beautifully written by professor of philosophy Olga Volkogonova).

Leontiev was perfectly capable of action. He received a medical education and, at age 24, volunteered to serve in the Crimean War as a military doctor. Although he did not see the fighting up close, he spent the winter of 1855 treating the wounded, which involved not only “helping the orderlies change bandages, verifying that the prescribed treatments were completed, correcting the medical inventory records” (Volkogonova, 63), but also difficult surgeries, decades before penicillin. As the war drew to a close, he turned his attention to more personal matters, eloping with his landlady’s daughter, Elizaveta Politova, who “could not show off much education, did not read books, had never heard of Turgenev or of literary salons, but was amazingly picturesque and utterly without the affectations common to young ladies in Petersburg! To add to that, she also beautifully sang romances and Greek songs…” (83) He would provide for her for the rest of his life (she outlived him by many years), through adversity and her mental illness, though, characteristically, he was not a faithful husband: vacationing for a few months in Constantinople, he immediately devised a plan to “free” a certain Lina from a brothel. Once settled in Yanina in the late 1860s, Leontiev invited his niece Masha to come live in his home; it is likely that they were lovers, also for many years.

(Volkogonova, 194-195)

There is more poetry in this one scene than in all of Leontiev’s writing, and really in most writing, by anyone. For a bookish, introverted young woman, barely twenty at the time, this was a moment to remember for the rest of her life. Most of us will never have the like. Poetry, and philosophy, too: a worldview. Years later, in one of his Warsaw articles, Leontiev wrote this passage, ostensibly with the goal of literary criticism, but unwittingly resonating with Masha’s travel impressions:

from The Warsaw Journal, 1880

Old Greek man wearing a fustanella. 19th century photo.

Old Greek man wearing a fustanella. 19th century photo.

Then, in another article, the same sentiment, with more humor but even more explicitly:

(Leontiev, 548-549)

Sympathy with the Ottoman Empire is a bit unexpected in a 19th-century Christian reactionary, especially one who became an Orthodox monk. Rozanov was perhaps the only critic who truly understood what it meant. In the late 1860s and early 1870s, Leontiev wrote a series of short stories that was eventually published under the title From the Life of Christians in Turkey. The content is a combination of ethnographic sketches, Orientalist fantasies, romantic adventures, and psychological portraits; perhaps one sign of its authenticity is that Leontiev shows a much better ear for dialogue here than in any of his other literary work. Unlike The East, this material is almost never reprinted, but Rozanov may be right that it shows much more of Leontiev’s essential nature than his journalistic or overtly philosophical writing:

(Rozanov, XIII/325)

I should note here that I spent some time to find the passage quoted by Rozanov. As I said, Leontiev’s fiction is out of print, aside from an academic collected works published in 2001, but some of it has been digitized. The exact quoted text does not appear anywhere in his Oriental prose, but the likely source for it is the story “Pembe,” where an old woman monologues, “I know the law. I see that I am old. I bought [her] for him myself… I moistened her soles with water and made her stand barefoot to see if the print she leaves is beautiful.” In other words, Rozanov was quoting inaccurately, from memory, in the process unconsciously embellishing the quote to make it even more quintessentially Leontiev-like (“the first condition of a woman’s beauty“), and thereby showing the kinship between them. And it is true, Leontiev’s actual stories are very much in this same emotional register:

from “Pembe,” 1869

Fortunately, Leontiev’s fiction is so obscure and so unread that we may be spared the usual lecture on Orientalism. Perhaps there is as much Byron in “Pembe,” and even more of Leontiev’s own fantasies, as there is genuine cultural knowledge (though, as Volkogonova explains, there is some factual basis for the story). But it is undeniable that he grants much greater depth of feeling to a religious other than he ever did to contemporary European culture, or, for that matter, to the Russian characters in his other, weaker literary work. And, if Rozanov misquoted him (intentionally or not), he certainly understood the rich sensual vein running through Leontiev’s prose, the blurring between physical and emotional love that 19th-century European literature was simply not allowed to depict in contemporary settings.

In 1892, a year after Leontiev’s death, Rozanov published a long critical essay about his work. As with much of Rozanov’s writing, however, the subject is more of a starting point than the real focus, but the title, “The aesthetic understanding of history,” would be a good name for Leontiev’s philosophy, if it needed one. Near the end, Rozanov writes, “Indeed, this is the universal and principal meaning of all of [Leontiev’s] writing: beauty is the measure of life, of its tension; but beauty not in some narrow, subjective understanding, only in the sense of diversity, expressiveness, complexity. All that exists in the universe, that appears in history, is subordinate to this universal and profound law; all that increases in abundance, diversity, and the firmness of its forms as it grows in its vitality; and, falling, returning to nonbeing — weakens in its forms, which become mixed, blend together, grow dim and finally vanish, leaving only the dust of the grave.” (Rozanov, XXVIII/112) Aestheticism was inborn to Leontiev; it was his first means of experiencing the world, the one he reached for instinctively, subconsciously, in every situation. Volkogonova gives a humorous summary of one of his earlier novels: “Volodya Ladnev admires a certain Nikolayev because his profile is ‘dry and noble,’ his linen is excellent, sometimes he wears ‘an elegant blue tailcoat with bronze buttons,’ and he greets Volodya at his home dressed ‘in a marvelous robe from black wool.’” (Volkogonova, 111) The equation of physical qualities with moral ones is another quality that strongly parallels Mishima. As a young medical student, Leontiev visits Turgenev, hoping for his literary patronage, and his greatest fear is that Turgenev’s appearance might turn out to be less heroic than his stature as a man of letters: “Leontiev was afraid that he might see a modest, unattractive man in a stained jacket, in a word, a ‘pathetic laborer.’ His fears were magnified by the fact that the protagonists of Turgenev’s works from that time were all ‘so modest and pathetic.’ In his old age, Konstantin Nikolayevich admitted, ‘From my youth I could never stand colorlessness, boredom and bourgeois plebeianism, even when I still considered myself to be a democrat.‘” (34)

The same aestheticism is present in Leontiev’s philosophy of history, now presented using more formal language and drawing on his medical knowledge:

from “Byzantism and Slavdom” (Leontiev, 180)

After which they begin to decline, decaying into simplicity once more. “Just before everything perishes, the individualization of both the parts and the whole weakens. What is dying becomes more monotonous internally, closer to the surrounding world, and more similar to closely related phenomena[.]” (182) And the same law, when applied to human culture, takes on an aesthetic dimension:

(Leontiev, 184)

And in the lives of nations it is the same as well: the “highest point of development” for a people is the moment in time at which they achieved the greatest “complexity,” understood both as distinctiveness from other peoples as well as internal “diversity,” i.e., the presence of multiple distinct, separated social classes. The existence of a distinct aristocracy and clergy is valuable to Leontiev because, to him, a greater “diversity” of individualized social roles speaks to the depth and “complexity” of the nation as a whole. Leontiev never singles out the aristocracy for being superior to any other class; he arguably expresses more frequent admiration for poetry in rural life, beauty in faces and clothes that are far from aristocratic. In fact, the presence of both, simultaneously, is equally desirable. “Then we see…a deeper or sharper (depending on the potential of the initial formation) divide between the classes, a greater diversity in everyday life and in the character of different provinces. At the same time, both wealth and poverty also grow — on one hand, the resources of pleasure also become more diverse, and on the other, this same diversity and the elegance (development) of sensations and needs lead to more suffering, more sadness, more mistakes and more great deeds, more poetry and more comedy; the feats of the educated Themistocles, Xenophon and Alexander are greater and more attractive than the simple and crude feats of Odysseus and Achilles.” (188-189)

In a way, this leads Leontiev into his own version of “cosmopolitanism.” Just as inward diversity (of social classes and roles) and outward complexity (of the arts) benefits the nation, so does the complexity of distinctions between nations benefit humanity as a whole. In discussing the aristocracy of various cultures, Leontiev lists “the eupatridae of Athens, the feudal satraps of Persia, the optimates of Rome, the marquises of France, the lords of England, the warriors of Egypt, the Spartiates of Laconia, the nobility of Russia, the pans of Poland, the beys of Turkey.” (189) From these groups’ own point of view, the kinship between them might be rather tenuous, but, in a sense, Leontiev is willing to celebrate any culture (thus his Turkish sympathies), as long as it remains within the outlines that distinguish it from every other. Rozanov completes his thought: “Sparta and Macedonia were below Athens in their historical roles; but if instead of Sparta, Athens and Macedonia there had been three different Athens — history would have been more meager for it. There is no need for a second or third Athens after the first.” (Rozanov, XXVIII/51)

Leontiev’s sensualism, his nationalism, his aestheticism, his philosophy, his fiction, and his religion all converge into a single endless yearning for every possible form of life. The sensuality of the Oriental harem is beautiful, but so is the chastity of European chivalry, the clarity of ancient philosophy, and the austerity of Christian monasticism. “Blossoming complexity.” An endless hunger for every form of human experience, all at the same time, and all at maximum depth. Rozanov felt that part of Leontiev, because it was also present in himself; there is a passage in Fallen Leaves where he goes so far as to deny that Leontiev had any interest in Christianity at all:

(Rozanov, XXX/180-181)

This is brilliant writing and characterization, and there is some truth in it, especially in the image of Leontiev waxing rhapsodic about love of women to an audience of Turks, monks, and bandits. But only some. First, if one’s goal was only to write polemical articles about religion and patriotism, one can always do that while completely abandoning one’s professed values in private life. Rozanov himself has many vitriolic observations of how the liberals of his time did exactly that. But Leontiev resigned from diplomatic service, spent a year on Mt. Athos, and left only because the monks did not allow him to take the tonsure there. His conversion was sudden, but by all indications sincere and intense. He wrote to Rozanov about it:

letter of August 13, 1891 (Rozanov, XIII/378)

Leontiev in the late 1880s.

Leontiev in the late 1880s.

Yes, if a man of passionate temperament were to decide to embrace religion, it would happen exactly like this. But it was not a momentary fancy. He destroyed his unpublished manuscripts, though he had always believed in his literary talent and hoped for success as a novelist. “Life on the Holy Mountain is severe,” especially for someone accustomed to comfort. “He ate little and slept little, together with the monks. Matins began in darkness, around five in morning. On feast days, vigils lasted the entire night. Leontiev could not adapt to the meager and crude food at the monastery — he became weaker, suffered from dizziness and stomachaches, later remembered how ‘the food exhausted me to the point where I could hardly walk.’” (Volkogonova, 228) Even if it had only lasted the one year, this is not something one does on mere impulse. But Leontiev really did transform his life. After his return to Russia, he moved close to Optina Monastery while continuing to provide for his entire extended family, of sorts. This included his wife, who by that point was far gone. “She did not bother her husband: like a little child, she obediently retired to her room, where she liked to play the guitar while he worked, for the most part was quiet and obedient. Almost every day, Lisa walked along the boulevards — in a dress, with unkempt hair, with a doll or a kitten in her arms — a kind forty-year-old child, who could so easily be not only gladdened (with a watermelon or with candy) but also hurt or frightened.” (351) Around 1884, Leontiev recorded the “final break with Masha” (348) in his journal; their relationship had turned sour years before then. His servants, their spouses and children, basically became part of the family and part of his responsibilities. He lived in poverty. There is a famously incendiary passage in Fallen Leaves where Rozanov contrasts his own well-being and that of his friends and comrades with that of various well-known liberals and opposition figures of the day:

(Rozanov, XXX/281-282)

One can only add that Leontiev’s life in Turkey was far from these dire straits, and he could have continued his diplomatic career and had a much easier time. Rozanov only knew him late in life, long after his conversion, when Orthodoxy had replaced all of his old preoccupations. Berdyayev wrote about Leontiev that he “turned [his] dark hatred of people and of the world into religious dogma, though in secret he loved, not people, no, but the sweetness of the world and often naively revealed this second half of his being,” (Leontiev, 16) but Leontiev willingly stepped into poverty when he didn’t have to, whereas Berdyayev himself was precisely the sort of man who never once denied himself “the sweetness of the world” and never had to worry about where his next meal would be coming from. In Rozanov’s financial division of the Russian literary world, Berdyayev would not have been same side of the ledger as Strakhov, Dostoyevsky, and Leontiev. A telling quirk of Leontiev’s final years: when he had secured his pension, bringing about “relative financial well-being,” he not only “helped others and loaned money to young acquaintances,” but also “attempted to repay his old debts, which the creditors had likely forgotten about. He tried to find his former kavass Yani, to return a small amount that he had borrowed from him in Turkey. He found the tailor Matveyev, whom he owed 50 rubles from back in his student days.” (Volkogonova, 373)

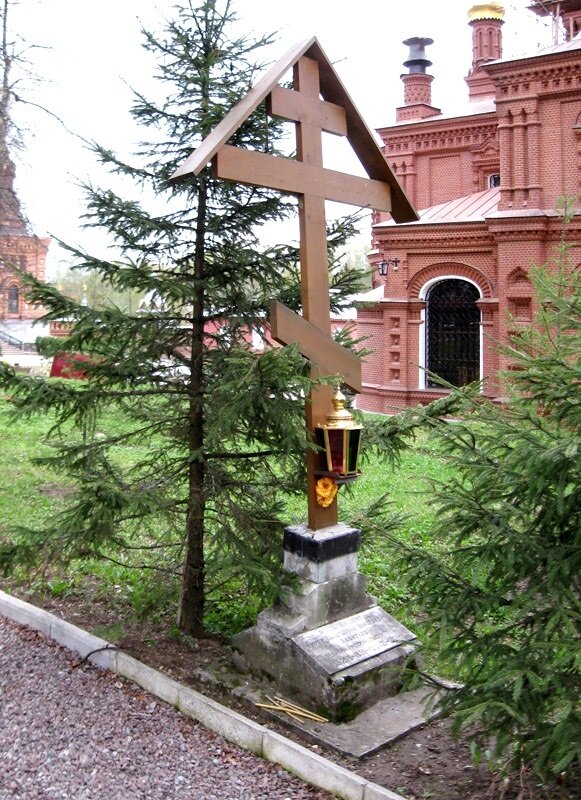

On August 18th, 1891, Leontiev was tonsured in secret at Optina Monastery, taking the monastic name Clement. “Leontiev, who had always preached a raging multitude of colors, disheartened by the fact that the house he lived in was painted white and not pink or orange, now wore only black — a monastic reminder of the necessity of repentance. Since he had long been dressing as a monk already, the appearance of a cassock in his wardrobe surprised no one.” (425) But he was not accepted into the monastery itself; St. Ambrose of Optina (canonized by the Russian Orthodox Church in 1988) instead instructed him to move to Sergiev Posad, home to the ancient Trinity Lavra of St. Sergius. He died there on November 24th of the same year, and was buried on monastery grounds. (By a twist of fate, Rozanov was later buried nearby, in 1919.) Masha returned to care for Leontiev’s ailing wife, who “died only after the October Revolution.” (436) Masha herself died in 1927.

What is there left to say? Later writers, commenting on Leontiev’s life, always had difficulty accepting his conversion. Rozanov, as we saw, did not even fully admit its sincerity. In a different essay, he wrote, “[His] was a tortured faith, far from childlike clarity and heartfelt simplicity” (Leontiev, 39) and also, “his life in [Ancient Greece] would have been completely different; its flow would likewise have been different by the side of the Byzantine autocrats. He was born talentlessly, born not for happiness. But…by the qualities of his soul, he was capable of living as the happiest of mortals, full of laughter, merriment, ‘outrage’ (he wanted that too much) and not once thinking about death or monasteries.” (40) Again this idea that Leontiev’s life had somehow taken a wrong turn, that he was never meant for monasticism.

Rozanov’s opinion is not easily dismissed; in addition to his usual perception, he had a special affinity for Leontiev’s form of thinking, for his aestheticism and sensuality, and understood him on a very deep level. And yet, Leontiev’s tonsure was blessed by an Orthodox saint, who undoubtedly saw whom he was talking to. So there is a deep significance in Leontiev’s religious life as well. Maybe the final question we should ask is what that is.

Let’s adopt Rozanov’s point of view — that Leontiev was a vast soul trapped in a narrow time, for whom “the further from religion, the merrier and more joyful. The southern sun floods his magnificent canvases with their depictions of Oriental life, and he willfully gives himself over to enamored charm, voluptuously absorbing the savory elements. But let the breath of religion rush past, and all darkens, black shadows fall, fear enters the soul.” (39) A kind of 19th-century Epicurean, a pagan sensate desperate to inhale every scent of life, hear every sound, feast his eyes on every color, before everything fades into “secondary simplification,” silence, and death. But then, such a man, rather than letting religion be just another phase, spending one year on it and moving on to the next fascination, systematically breaks himself, gives up his beloved material pleasures one by one, and ultimately becomes a monk, while scrupulously maintaining his obligations to all the household members that he had previously gathered together in such a messy fashion. For this, he does not even receive the compensation of religious comfort, as many monks do, because, as Rozanov observed, Leontiev’s faith did have a strong element of “fear.” If he ever felt at peace, he didn’t say it in writing. In fact, he rarely wrote about Orthodoxy directly; The East contains one biographical sketch, “Fr. Clement Sederholm, hieromonk of Optina Monastery,” in which Leontiev shows some of his own religious experience through the person of a monk whom he respected, but even for this purpose, he chose a subject who “did not know how to calmly lead and support others,” (Leontiev, 323) who was born in a German Protestant family and always felt more comfortable with rational rather than mystical life. Perhaps he felt too inadequate to write at length about St. Ambrose or other such figures, and, when he dared to approach Orthodoxy at all, it was only through a man with more modest spiritual gifts.

What does one call all of this? A sacrifice.

Leontiev gave up more than “vices,” because his sensualism was more than a set of more or less pleasant pastimes — it was his entire way of understanding and interacting with the world. His philosophy of “blossoming complexity” is ultimately built on the senses. Without that complexity, there is no point in life and really no life at all, because the loss of it is the principal sign of death. And he gave it up, in the name of a holiness that he himself was not equipped to perceive, a salvation whose joy he was not capable of feeling. When Berdyayev wrote that Leontiev “did not love God and blasphemously denied his goodness,” (15) it was nonsense in the literal sense, but perhaps it might be said that Leontiev did not know how to love God and lacked the ability to feel His goodness. But that does not mean that he failed in religion. To sacrifice your very essence, in the name of faith, but without faith is, in a different sense, a radical act of faith. Leontiev was right — “the expressiveness of life” means far more than “stones.” The philosophy of life means far more than the philosophy that is written. Leontiev’s philosophical significance is in what his writing did not say, in everything that was too deep and too beautiful to be neatly argued and systematized. Remember, O Lord, Thy servant, the monk Clement, and pardon all his sins, voluntary and involuntary.

(Leontiev, 893)

so glad to see you post something new. you’re one of my favourite critics.

LikeLike