Sergei Esenin, 1920

(Continued from part 1.)

Runaway Horses is Mishima’s “right-wing” novel, deliberately written in a way that parallels the author’s own death (which, most likely, he had already planned out at the time of writing). There is no way to avoid it, and it cannot but be read as autobiographical.

Indeed, it is universally seen as a personal statement, though really, as Rankin says, “Mishima’s death also affects a permanent change on his literary works, every one of which now appears to point inevitably to this moment, as if every word he had written was posthumous.” (Rankin, 172) Paul Schrader’s film Mishima: A Life in Four Chapters explicitly equates Mishima’s life and work by interspersing three reenactments of different novels among its biographical segments. One of them, inevitably, is a fifteen-minute summary of Runaway Horses, presented in a style so garish that it might be a parody (curiously, it is also inaccurate — Isao never claims to have been “chosen“). For Rankin, likewise, it is a certainty that “it is almost impossible to read…the novel in which Mishima chronicles the career of a right-wing terrorist in the 1930s, without superimposing our knowledge of the author onto the protagonist. That is just what Mishima intends.” (158)

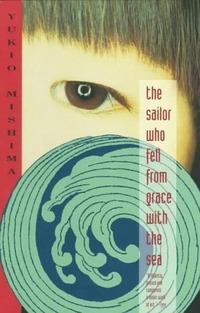

Both Schrader and Rankin, and every Western critic who has written about Mishima, understand that Isao’s motives (and, therefore, Mishima’s motives, since they view them as identical) are not narrowly political. Rankin, as we have seen, subscribes to the common interpretation of Mishima’s political activity as just one facet of a grand narcissistic art project, and to him Runaway Horses is a straightforward statement of intent: “The one clear objective in [Isao’s] mind is aesthetic: he wants to kill and he wants to die beautifully. Terrorism is the means whereby he actualizes this narcissistic vision.” (159) It is thus made to fit neatly into a long line of novels by Mishima which describe “gratuitous crimes, irrational crimes, inexplicable crimes, motiveless crimes.” (61-62) In this paragraph, Rankin again names Runaway Horses as an example, alongside The Sailor Who Fell From Grace with the Sea (1965), in which “a group of teenage boys murder a sailor and dissect his corpse, having judged that he lacks heroic potential,” (62) this time without any political motivation.

At first glance, this is quite plausible. Indeed, there are plenty of malevolent, destructive characters in Mishima’s novels, and there are clear parallels between Isao and Noboru in Sailor. Both are young, both have set themselves apart from society, both envision and idolize fantastical heroic figures, both have no qualms about killing, and for both, killing becomes a form of rebellion against a world that fails to live up to their ideal. In fact, the similarities are even deeper than that. Isao says, sincerely, “By this action the souls of those whom we cut down would also become pure, and the bright, wholesome Yamato Spirit would come alive in their hearts again. And they, with my comrades and me, would rise to heaven.” (Runaway Horses, 394-395) And for Noboru, as well, murder is a way to “make that sailor a hero again[.]” (Sailor, 135) Rankin does not pick up on this theme, perhaps because it is less straightforwardly “narcissistic,” but one could argue that it makes his reading even more compelling.

But there is one problem: Noboru is a parody of Isao, and, if we accept that Isao is a stand-in for Mishima, then Noboru is also a self-parody of the author. He repeats (or, rather, presages, since Sailor was written earlier) Isao in many ways, but he is a laughable, pathetic figure. He first forms his idealized image of the sailor while hiding inside a chest of drawers and peeping into his mother’s bedroom. When his disappointment begins, he writes down the following list:

(Sailor, 81)

Noboru then strikes out the third item, because, “The subjective problem in the third charge was only proof of his own immaturity, not to be construed as a crime on Ryuji’s part,” (Sailor, 81) but this earnest deliberation makes the scene even more ridiculous. In any case, by the end, the number of charges increases to eighteen. Noboru shows the list to the “chief” of his group of friends, who pores over it with hilarious pedantry: “‘This is awful,’ the chief mourned. ‘This last one alone is worth about thirty-five points. And the total — let’s see — even if you go easy and call this first charge five points, they get worse the closer they get to the end. I’m afraid the total’s way over a hundred and fifty. I didn’t realize it was quite this bad. We’re going to have to do something about this.’” (161) However much Mishima may have sympathized with the “purity” of Noboru’s hatred of the world, as a writer he undoubtedly knew that this image, in which a numerical score is laboriously assigned to each of Ryuji’s failings, could read only as comedy. It stands to reason that he wanted it to be comical. But, if that is the case, then perhaps he viewed Isao that way too, or at least was able to look at him from that point of view? Maybe there is some parody in Isao as well? After all, the first time we see him alone with his friends (and future co-conspirators), their meeting goes like this:

(Runaway Horses, 138-139)

One may be tempted to read this passage completely straight, because Mishima maintains an even, sympathetic tone (and, of course, because we already expect Isao to be the embodiment of his own views). But he did the same thing in Spring Snow when describing Kiyoaki’s teenage tantrums. One should never read Mishima too credulously. Of course he can see that Isao’s righteous indignation has a significant element of play-acting, whose silliness in no way diminishes its sincerity or the severity of the consequences. (As we know from Huizinga, nothing is more serious than play.) By poking fun at it in this way, he also acknowledges the same element of absurdity in his own “political” activities, which, unlike Isao’s, did not have the justification of youthful purity.

Over the past fifty years, Mishima has become a symbol of national pride as an idea in itself, one that is completely detached from Japan. But a true knight is unafraid to face reality in all of its dimensions; though some of what I say may have a bitter taste, still we must reach for a deeper and truer understanding. First it is necessary to understand that Mishima’s actual view of right-wing politics was, at the very least, suffused with irony. Some unexpected insight into it can be found in Kyoko’s House. The boxer Shunkichi is down on his luck after his promising career was cut short by an injury. He wanders around Tokyo with nothing to do — “His strength, the foundation of his being, had already vanished” (Kyoko’s House, 410) — until he stumbles upon “Masaki, a former classmate, leader of the fan club,” (412) who takes him out to lunch and convinces him to join a right-wing “society for the defense of Greater Japan.” (421) The arguments that he presents, however, would have been shocking to Isao:

(Kyoko’s House, 416-418)

This passage is also a good example of Mishima’s inclination to put statements that we expect him to uphold (the ones about dissolving in death) in the mouths of characters whom he despises. Masaki’s love of money is not an incidental detail — think of how a proper samurai should look upon material gain. The juxtaposition of patriotic rhetoric with materialistic cynicism is therefore very deliberate. In Runaway Horses, Iinuma expresses very similar sentiments: “I heard that…there was a flood of petitions asking leniency. So the naïve purity of the young defendants will surely evoke public sympathy. We can count on that. And my boy, rather than losing his life, will come home covered with glory. His whole life long, he’ll have no worries as to where his next meal is coming from. Because the world will forever hold him in awe as Isao Iinuma of the Showa League of the Divine Wind.” (Runaway Horses, 316) This is, of course, the same Iinuma who was humiliated by both Kiyoaki and his father in Spring Snow, who married Miné but continued to resent her for having been compelled to share Marquis Matsugae’s bed. He now runs an establishment called “The Academy of Patriotism,” which has “some ten or more students” (132) but whose curriculum, quite pointedly, is never described (even though, in Spring Snow, the author saw fit to write down the entirety of a dinner menu). It appears to consist mainly of athletics with a smattering of ideological color.

Mishima, like Isao, was a kendoist.

But then, it is not surprising that frauds would be attracted to any movement that makes its appeal to high-minded idealism, and that is not what Mishima wants to portray in Runaway Horses. Betrayal runs far deeper, in many layers. The conspiracy begins when Isao somehow meets an army officer, Lt. Hori, and gives him a copy of his favorite book, a right-wing pamphlet describing a samurai rebellion during the early Meiji era. Hori then writes to him that he “had found The League of the Divine Wind quite stimulating…and since he wanted to share it with his friends, he was keeping the book at the regimental headquarters. He would be happy to see Isao any time that he wished to come to retrieve it.” (148) When they meet in person, Hori’s apparent sympathy and admiration easily draw out all of Isao’s beliefs, causing him to immediately reveal his hope for a similar rebellion in the present day. Isao wastes no time in asking Hori, not simply for moral support from the military, but for direct involvement, which, in his opinion, should include an air strike on the “corrupt” districts that he had marked in purple. Hori vetoes that idea, urging “the substitution of flares and leaflets for bombs,” but he promises “that his staunch friend Lieutenant Shiga would participate.” (258) The preparations proceed, until, without warning, and with less than a month remaining until the date planned for the uprising, Hori summons Isao and commands him to call off the plan entirely. The nominal reason is that Hori is about to be transferred to Manchuria, but he also complains about “deficiencies in planning, the inadequate number of men involved…the project’s premature timing” (278) and other factors that had always been in plain sight from the very beginning. The following exchange takes place:

(Runaway Horses, 277-278)

But what Isao doesn’t seem to realize is that, if Hori is able to say this now (i.e., that he wants to take part in a violent rebellion, but can’t because the date is inconvenient), then there was never any time when he had taken the plan seriously. For him, everything had always been leading up to this moment — he had encouraged Isao’s group only so that he could now order them to quit. But why would Hori, whose life is fully occupied with the routine of a military career and who therefore has better things to do, ever want to waste his time in this way? Clearly, only because he had been ordered to do so. In other words, we are looking at a political provocation, one that doesn’t even bother to disguise itself. The military is using the respect that it commands among young militants to rope them in with crude flattery and empty promises. Perhaps the intention is merely to monitor them, to convince them to redirect their energies toward conventional military service if possible, and to make it easier to arrest them if they get too unruly (which indeed is what happens with Isao). This also explains why Isao gets off with basically a slap on the wrist. Ironically, he finds himself envying the communists who are being tortured by the police, because, unlike him, their beliefs are being viewed as a genuine threat.

But that is not all that can be done with the young and pure of heart. Shortly after their first meeting, Hori brings Isao to see Prince Harunori Toin, the same personage who was supposed to have married Satoko in Spring Snow. This is a very strange meeting. Hori’s rank is not nearly high enough for him to be casually socializing with members of the imperial family, to say nothing of bringing along a teenage boy from a rather humble background. Nonetheless, the prince receives them quite warmly, condescending to criticize his own class in front of them: “The nobility, too, is guilty. It sounds splendid to call the nobility the ‘living ramparts’ of the Imperial Family, but there are those among them who, sure of their power, tend to even make light of His Sacred Majesty… And as for the necessity of chastising the overweening pride of those who should be the mirror of conduct for the common people, here, especially, I am entirely of the same opinion as you.” (185) He then turns to Isao and asks, “Suppose…suppose His Imperial Majesty had occasion to be displeased with either your spirit or your behavior. What would you do then?” (186)

In other words, right-wing activism has its uses. A prince who is able to strike a rapport with fanatical patriots like Isao can then turn them into his own personal guard. They could be used to terrorize obstinate financiers, for example, or other aristocrats who overstep their bounds. At least, it is worth suggesting the idea to an ambitious young lieutenant who can be easily flattered by the feeling of “a freedom that came of their both being military men,” (184) just as the lieutenant himself flatters Isao by professing admiration for the League of the Divine Wind. As for why Toin chooses not to go any further, perhaps it is simply out of cowardice — the slightest hint that his name might be connected to Isao’s case fills him with fear. “And of all things to use my name! To exploit my name that way after a single meeting, the name of an imperial prince! He’s lost all sense of obligation… Is this his concept of loyalty? Of sincerity? How distressing that young men are like that!” (329)

There is a third option as well: gathering together the most passionate,

There is a third option as well: gathering together the most passionate,

most obstinate part of the populace simply to dispose of it.

I wonder what fate befell this Isao.

But, while right-wing groups may be useful to the nobility for keeping the capitalists in line, it turns out that the capitalists themselves are also very willing to hire the patriots who hate them. Near the end, after Isao’s trial and near-acquittal, Iinuma reveals:

(Runaway Horses, 406-407)

Sawa, mentioned in this passage, is another very strange figure, a middle-aged man who has a family somewhere in the countryside, but lives in Tokyo and has enrolled in the Academy for some reason, spending all of his time lounging around, reading pulp novels and watching the students. He ingratiates himself into Isao’s group, first vaguely hinting at Kurahara’s connection to Iinuma, then making a show of fervor and demanding that he alone be assigned to assassinate Kurahara. When Hori backs out of the plan, Sawa produces a large amount of money seemingly out of thin air. He is arrested with Isao and the others, but is released quite easily. In short, he is an obvious informer working for Iinuma, for Kurahara, for the police, or for all three — and, in any radical youth organization, whether left-wing or right-wing, whether in the 19th century, the 20th, or the 21st, there will always be just such a slippery middle-aged man with a murky background present at every meeting.

Kurahara appears in one scene, where he expresses views that have not changed at all in 100 years, and probably never will: “Stringent economic measures are never popular, and any government policy that embraces inflation is sure to gain the favor of the people. For our part, however — we who know what is the ultimate happiness of this ignorant race of ours — we must strive with this ever in mind even if a certain number of people unavoidably are victimized… Since economics is not a benevolent enterprise, one must foresee that some ten percent will become victims while the remaining ninety percent will be saved.” (168-169) The particulars may change — sometimes these people are for inflation, other times against it — but the conclusion always remains the same. And people like Iinuma can be quite valuable to them. They channel the anger and despair of the “ten percent” (actually much more) for whom there is no place in the grand designs of public policy, and Kurahara can simply pay to redirect their wrath onto one of his rivals and competitors. There is no shortage of targets, after all, so they can take the money without even having to feel that they are compromising their beliefs; as Iinuma says, “To defile yourself, yet not really be defiled — that’s true purity.” (408) Of course, Kurahara’s enemies do the same to him: when one of Iinuma’s younger students shows Isao a “folded-up tabloid newspaper” (400) attacking Kurahara, it never occurs to him to wonder who might be bankrolling it.

So, when Mishima wrote in “one of the manifestos…for the Shield Society” that, “Effectiveness is not an issue for us, because we do not think of our existence or our actions as constituting progress toward the future,” this was a carefully considered position with deep practical significance. Rankin’s reaction is amazement: “A militia that does not care about its own effectiveness!” (Rankin, 163) But the moment that Mishima’s group became “effective” would also be the moment of its infestation by Sawas and Iinumas, its co-optation by Shinkawas and Kuraharas, until there were more informers than actual members. Unfortunately, the individual, so long as he remains an individual, has no chance against state power. The parodic, harmless nature of Mishima’s organization, the live-action role-playing aspect of it, was the only way to ensure at least some nominal form of independence. And perhaps his suicide was the only way to definitively prove his own agency; at least, in Runaway Horses, that reading of Isao’s death practically invites itself. Isao experiences the collapse of his ideals, analogously to how Kiyoaki in Spring Snow undergoes the devastation of love. It is now clear to him that assassinating Kurahara will accomplish nothing: “I’ve lived for the sake of an illusion. I’ve patterned my life upon an illusion. And this punishment has come upon me because of this illusion…How I wish I had something that’s not an illusion.” (Runaway Horses, 409) For Isao, it becomes something like Kiyoaki’s walk to the doors of the Gesshu Temple, and suicide becomes the only escape from the script into which his life has been forced by the stage managers of life in 1930s Japan.

Really, that script had been written long before he formed the conspiracy. The very idea of it was, itself, always part of the script. The single greatest influence on Isao’s thinking is the book The League of the Divine Wind — it is so important to him that the full text of it is included, verbatim, in the novel. In other words, Mishima took the trouble to write a book within a book, putting the plot on hold for 50 pages and going off on a tangent about a rebellion from 1876. It is crucial to remember that this is not a flashback or a parallel storyline or some such literary device, but a book that Isao has read. Its author is not “Mishima” in the sense of the third-person omniscient voice that narrates the rest of the novel, but a specific character, one Tsunanori Yamao. Nothing is known about this man, except that he is most likely Isao’s contemporary. The League of the Divine Wind is not a primary source; it was not written by a participant or survivor of the rebellion, though it claims to draw upon such writings. It is a recent work, whose subject is the distant past, but whose intended audience lives in the present day.

It would not be entirely accurate to say that League is poorly written — to borrow a phrase from Charles Kinbote, Mishima could not write otherwise than beautifully — but it is bad literature. In describing the samurai heroes, Yamao at least tried to think of some details to make them stand out, but he felt no need to do the same for their wives: “When she was sixteen, a certain wealthy man desired her as his bride, but since Ikiko had resolved to marry only a militant patriot, she was not at all inclined to assent.” (103) In other words, this is a very crude ideological text deliberately targeting young men like Isao, who have no experience with women, and for whom the nationalist dream and the romantic one have to be realized together. Indeed, when Isao feels unsettled by a beautiful woman’s gaze, his way of impressing her is to address his friends, “his outlandish tone altogether unsuited to the setting: ‘Listen to me, you two. If in Japan today you could kill only one man, who do you think it would be best to kill?’” (146) And Makiko deliberately plays into his fantasy, knowing that he wants her to be someone like Ikiko from the book — her reply, the irony of which seems obvious in retrospect, is “Evil blood…is blood that cries to be shed. And those who shed it may indeed heal our country’s sickness” (147) — but ultimately she betrays him as well, by lying at his trial.

The sheer amount of space devoted to the text of League makes it very conspicuous that no information is ever provided about its author. It did not have to be that way — perhaps the pamphlet could have included a brief biographical sketch, saying that Yamao was a scholar of history, or a patriotic philosopher, or a military veteran, or a Shinto mystic, or something else that the audience would have respected. And there is no reason why the book could not have been written by such a person. But there is nothing, which raises the possibility that Yamao may not exist at all. In other words, the book is anonymous, lacking even the substance of an author’s personal affirmation. Isao’s absolute sincerity is based on a total mirage.

While League appeals to traditional Japanese values, in reality it exemplifies contemporary revisionism. Countless “Academies of Patriotism” have sprung up overnight, but their connection to actual Japanese culture is quite questionable. All that we are ever told about what Iinuma does in his classroom is that, “In teaching his classes, Iinuma was fond of using the expression ‘love for the Emperor.’” (177) He also arranges field trips to visit similar organizations, one of which, “a training camp…on the rites of purification,” (240) is described in a bit more detail. The proprietor of this establishment specializes in hostility to Buddhism: “And then, the compliments out of the way, he immediately began to lash out at Buddha: ‘I realize that we have only just met, but, really, that fellow Buddha was a fraud. I suspect he’s the rascal that robbed the Japanese of their Yamato Spirit, and their manly courage. Doesn’t Buddhism deny all spirit?” (242) The author of League is more polite in this regard, but he, too, emphasizes that his heroes “resolved to make known to all the ancient Shinto ritual as preserved in the classics and, by so doing, to set right the hearts of men and restore the pure land of the gods, a land blessed with the divine favor.” (65) Both of them derive their views from the same 19th-century thinker, Hirata Atsutane, for whom anti-Buddhism was also a revolutionary program masquerading as a traditionalist one, a philosophical basis for rejecting the authority of the shogun and preparing the way for the Meiji Restoration (which, of course, was not a “restoration” at all, but a radical modernization, very similar to the reforms of Peter the Great).

Many historical Japanese temples combine elements

Many historical Japanese temples combine elements

of both Shintoism and Buddhism.

Undoubtedly, there was some tension between Buddhism and Shintoism throughout Japanese history, but it is clear from Spring Snow that this issue was nowhere near the cultural forefront twenty years ago. On the contrary, Shinto rituals are woven into the daily life of the Matsugae house, but everyone also accords the utmost reverence to the Abbess of Gesshu. In general, the world of Spring Snow is quite secular, so that Kiyoaki and Honda are even surprised by the Buddhist fervor of the visiting Siamese princes. Honda’s mother is a member of a patriotic organization, but it does not seem to have much religious or militaristic content. This is still the world of Natsume Soseki, a world of literary salons, movies, and serialized novels, and overall it feels very similar to any European country of the time.

But by the time of Runaway Horses, Japanese culture has been deliberately archaized. The reason, of course, is that the ruling elite knows that a world war is coming and is rushing to prepare for it. For their narrow purposes, Shintoism was more useful than Buddhism because it could be made to accommodate a kind of ruler-principle. As Rankin points out, “the conception of the Japanese emperor as a living god was no more than a short-lived modern myth. While Japan’s most ancient written documents assert that the imperial dynasty has a divine origin…they make no claim for the divinity of individual emperors. Each was a human being whose ancestors were gods. The emperor was a mediator between the Japanese people and their numerous deities, a sacred figure but not a god… Religious reverence for the emperor became a vital element of Japan’s wartime propaganda policies.” (Rankin, 155) The League of the Divine Wind is not simply a work of patriotic literature, but a small piece of a massive infrastructure constructed by the state. There is still a large class of Westernized specialists in Japan, but even someone as wealthy and powerful as Kurahara is not beyond the reach of the new system of militaristic literature, newspapers, and training camps. The “tabloid newspaper” that attacks Kurahara is part of that mechanism as well — it is primitive, “crudely printed, with broken type evident here and there,” (Runaway Horses, 400) but that suffices, because all it takes is one undiscerning, overzealous, gullible young reader. Soseki would never have gotten away with publicly turning down an honorary doctorate in the 1930s. Had this happened, no doubt similar articles would have been written about him.

Painting depicting the Shinpuren Rebellion.

Painting depicting the Shinpuren Rebellion.

It took some intellectual acrobatics to turn the samurai rebels in League into heroes of Japanese tradition. From the viewpoint of the Meiji era, they were outlaws; the only opponents that they ever killed were the emperor’s own conscripts. Both Hori and Prince Toin even point out the incongruity between Isao’s patriotism and his reverence for a group that attacked the Japanese military: “‘But I’d like to put one question to you,’ said the Lieutenant with a faintly ironic smile. ‘When it comes time for you to fight somebody, are you going to be like the League and pick the Imperial Army?’” (152) But then, from the emperor’s point of view, perhaps it is not good for the young fanatics to identify themselves with the military too much — they should depend on him alone. Each group has its own place. The military should fight overseas, the capitalists should develop the economy, the fanatics should keep them on their toes, and a delicate balance between all of them should be maintained.

The stated goal of Isao’s uprising is “to place finance and industry under the direct control of His Imperial Majesty,” (256) but they had always been under the emperor’s direct control. In the end, Kurahara is just another functionary, useful to the emperor as a lightning rod for the public’s discontent. When Isao finally managed to kill him, the imperial apparatus quickly appointed a replacement and forgot that he ever existed. The greatest, most hopeless betrayal of all, the one that even Isao doesn’t realize, is not that the capitalists were secretly financing his father’s business, but that the capitalists themselves were the creation of the emperor. The greatest betrayal of what Isao believes to be the Yamato Spirit is the one committed by the emperor himself. In fact, since he possessed absolute power, it can be said to be the only betrayal.

Mishima explored this theme more directly, in a short story whose title Rankin translates as “Voices of the Heroic Dead.” It is a stylized, declarative lamentation in which two groups of spirits confront the emperor with accusations. The second group consists of kamikaze pilots who perished during World War II, and who now reproach the emperor because they feel that his surrender rendered their sacrifice meaningless. “No matter how pressured or coerced, even if threatened with death, His Majesty should not have said that he is a human being.” (Rankin, 153) Like John Nathan several decades earlier, Rankin focuses on this group, narrowly interpreting the accusation as being focused on Japan’s defeat in the war and Hirohito’s public admission that, to quote the National Diet Library, “he is not a living god and that the concept of the Emperor’s divinity is not true.”

But there is also a first group, which Rankin himself describes as “the spirits of the young army officers who were executed after the failed rebellion of February 1936[.]” Their complaint is as follows: “At that time, Japan, the great land of abundant rice, had turned into a barren wasteland. The people were crying from starvation, women and children were being sold for money, and the imperial domain was everywhere filled with death.” (Rankin, 151) Rankin doesn’t make the connection, but it is hard to imagine any way to state it more clearly: the two groups of spirits are brought together because their grievances are two sides of the same coin. Hirohito was defeated and forced to abandon his divinity in 1945 because, earlier, he had failed to rule in a manner befitting the Japanese emperor. Or, to put it a different way, he had already “become a human being” (154) in 1936, and 1945 was merely when he was forced to finally admit it. The officers in the first group explicitly state, “That was the moment when His Majesty’s great army perished. That was the moment when Japan’s great moral law collapsed.” Rankin criticizes this story on the grounds that “Mishima makes the spirits of the heroic dead speak in an unappealingly harsh and jingoistic language. Some readers have said it is reminiscent of Japan’s wartime propaganda fiction,” (151) but that can just as easily be seen as a particularly cutting, brutal form of irony.

In fact, Mishima had engaged with the failed 1936 rebellion before, in the infamous story “Patriotism,” whose plot is summarized by its first sentence: “On the twenty-eighth of February, 1936…Lieutenant Shinji Takeyama of the Konoe Transport Battalion — profoundly disturbed by the knowledge that his closest colleagues had been with the mutineers from the beginning, and indignant at the imminent prospect of Imperial troops attacking Imperial troops — took his officer’s sword and ceremonially disemboweled himself in the eight-mat room of his private residence… His wife, Reiko, followed him, stabbing herself to death.” (Death in Midsummer, 93) Most of the story consists of a graphic description of their suicide; like Runaway Horses, “Patriotism” is often seen as autobiographical, especially since Mishima also filmed an adaptation of it in 1966 with himself in the leading role. Rankin sees “Patriotism” as an expression of Mishima’s morbid eroticism. Perhaps it is that, but we may also recall that, in the samurai mythos, seppuku was also seen as an honorable way for a warrior to admonish his lord when the latter’s actions were unworthy. Why has no one ever read “Patriotism” in this way? Instead of dying to expiate “the supreme transgression of defying an imperial command,” (Rankin, 108), perhaps the officer dies to attain absolute moral superiority over the emperor, who has brought Japan to such a state. And the detailed description of his suicide, Mishima’s insistence on its purity and perfection, is needed to prove that nothing sullied this moral ascent.

During the meeting with Prince Toin, Isao has a chance to expound on his understanding of loyalty:

(Runaway Horses, 187-188)

This may be the most duplicitous passage in all of Mishima’s work. It is couched in the language of subservience to the supreme leader, but really it asserts the power of the individual to assume the leader’s authority at his own discretion. To the modern omnipotent state, “unsanctioned loyalty” is worse than open rebellion — it is a usurpation of the leader’s exclusive right to decide what loyalty is, and where and how it should be demonstrated. But to Mishima, if there is any “sin” in this, it is washed clean by death. The all-powerful emperor can do nothing to the lowliest servant, provided that the latter has killed himself properly. And, of course Isao would never dare to think this, but if the emperor had been unworthy to begin with, the servant’s death lays bare his own dishonor. It is a form of “loyalty” that gives the servant the right to sit in judgment of the master.

From Mishima’s adaptation of “Patriotism.”

From Mishima’s adaptation of “Patriotism.”

Mishima’s nationalism is a radically individual experience. In that it really is like love. No one loves the nation like the nationalist, no one loves him the way she does — she is the one woman who will never betray him. Alone with his thoughts in prison, Isao wonders whether, “Perhaps there was some unwritten law of human nature that clearly proscribed covenants among men.” (Runaway Horses, 336) Perhaps not in all cases, but an intensely personal feeling like Isao’s patriotism cannot be the substrate for a political movement. Politics is an impersonal mechanism, even (especially) when killing. You must remember this if you ever decide to get involved in it; one day your life may depend on the knowledge.

But Isao’s destiny is different. For all that Runaway Horses is supposed to lay out Mishima’s personal program, for all that Rankin touts the “irrational” aspect of Isao’s violent urges, the truly wild and irrational heart of the novel has nothing to do with its political content.

Spring Snow contains the following description: “The moon shone with dazzling brightness on Kiyoaki’s left side, where the pale flesh pulsed softly in rhythm with his heartbeat. Here there were three small, almost invisible moles. And much as the three stars in Orion’s belt fade in strong moonlight, so too these three small moles were almost blotted out by its rays.” (Spring Snow, 43) It seems like incidental detail. But, twenty years later, Kiyoaki’s school friend Honda, now a “junior associate judge” (Runaway Horses, 3) with a promising career, happens by chance to attend a kendo competition in which Isao is taking part. After the match, walking by the waterfall where Isao and other young men are undergoing a Shinto ritual, “he happened to glance at young Iinuma’s left side. There…at a place ordinarily hidden by the arm, he clearly saw a cluster of three small moles.” Honda then remembers that Kiyoaki’s last words, as he died of fever, were “I’ll see you again. I know it. Beneath the falls.” (40) In other words, Isao is none other than the reincarnation of Kiyoaki, born to Iinuma and Miné a short time after the end of Spring Snow. And, like Kiyoaki, he dies at the age of twenty.

This is an extremely disquieting development. Mishima rarely delved into the supernatural. “Voices of the Heroic Dead” does not count, because it is a rhetorical piece that was obviously never intended to be viewed as a work of realism. However bizarre Mishima’s characters may be, they are almost always depicted in recognizable, even mundane settings. The disturbed acolyte in The Temple of the Golden Pavilion is, in one sense, a completely ordinary young man whose surroundings are absolutely typical of a Buddhist temple. The flamboyant nihilists in Kyoko’s House live in 1950s Tokyo. Spring Snow is painstakingly realistic, down to the clothes and the food. So is Runaway Horses, in every way other than this one. And yet, in this tale of political violence in 1930s Japan, there is another, inexplicable force, and sometimes it intrudes into the narrative with terrifying clarity:

(Runaway Horses, 374-376)

Kiyoaki’s dreams, which seemed like lyrical diversions in Spring Snow, now come to life. In one dream, “Kiyoaki was standing in the middle of a road that led through open fields. For some reason he was wearing a white cotton kimono and matching hakama, a costume he had never once worn, and was armed with a hunting rifle… At that moment, the light filmed over and a huge flock of birds appeared in the sky. When they reached a point above his head, filling the air with their squawking cries, he aimed his rifle upward and pulled the trigger,” (Spring Snow, 235) and then was accosted by “a group coming his way along the road…As they did so, he was startled to recognize the face of his former retainer Iinuma in their midst.” (236) Twenty years later, Honda, who has preserved Kiyoaki’s dream diary all this time, happens to be present at the anti-Buddhist “training camp” while Isao goes off with a rifle and shoots a pheasant, as a way of preparing himself for the uprising, in violation of the Shinto precept concerning “the defilement brought about by the flesh and blood of beasts.” (Runaway Horses, 248) Iinuma and his entourage come after him, and Iinuma scolds his son exactly as he had Kiyoaki in the dream.

I believe in neither reincarnation nor prophetic dreams, and I would also advise you not to; the life of Philip K. Dick is too stark a warning. Nor am I convinced that Mishima really believed in them. But, from a purely literary standpoint, this scene is chilling. Regardless of what he really believed, it is clear that this is the hidden, beating heart of Runaway Horses. The mystery of Spring Snow has only grown since Kiyoaki’s death, taking root in reality like a tree sprouting from a crack in a massive boulder, eventually crushing and fragmenting it into tiny pieces.

Honda, serving as a representative for the reader, dutifully engages with this problem, at turns denying it, explaining it using Buddhist theology, and attempting to grasp it intuitively: “It was Kiyoaki’s beauty alone that would truly occur but once. Its very excess made a renewed life essential. There had to be a reincarnation. Something had remained unfulfilled in Kiyoaki, had found expression in him only as a negative factor.” (215) None of these directions provides a satisfactory resolution, and Isao’s life burns out too quickly for anything definite to be ascertained.

I am not sure that the problem can be resolved. In any case, whatever answer we might name now, we will likely say something different for The Temple of Dawn, and again for The Decay of the Angel. But, for the moment, let me offer one interpretation specifically for the world of Runaway Horses. Isao’s reincarnation is the only part of his existence that breaks out of the track that had been built for him. Everything else that happens in the novel was, indeed, “destined,” but not by heroic fate — rather, Isao had been condemned from birth to follow a mechanical schedule pre-planned by a heartless 20th-century industrialized empire. According to that plan, he was always meant to be one of Kurahara’s “victims,” meant to seethe in resentment, meant to come across The League of the Divine Wind or another one of the many such texts that had been prepared for him, meant to seek out and fall for Hori’s provocation, meant to fail and be arrested. Perhaps, as Iinuma suggests, he was then meant to be honored for his failure, becoming a harmless celebrity dissident through whom other dangerous young men could be neutralized. And then, 12 years later, he could have died in a bombing, or lived on as a decrepit old wreck, like his father in The Temple of Dawn.

But there was one thing that the architects of this dismally predictable life were not able to foresee — an unfathomable force, greater than the capitalists and emperors, that unbeknownst to them had created Isao and that would violently sweep in again to bear him away from their dreary world. Beauty exists, no matter how they try to eradicate it; traces of it persist ineffably in the empty space left between the bars of the cage. A single invisible point suddenly explodes with light, and drab reality crumbles, having no substance of its own to offer. Beyond that instant are the faithful wife, the glorious nation, the just Emperor, welcoming their hero.

(Continuation: part 3.)

Fantastic essay. Glad to see you’re back in this new year.

LikeLike

Thank you for staying.

LikeLike

Thank you for continuing to write. It’s hard to describe how you have helped clear my eyes, I am a more mature person by experiencing your thoughts.

LikeLike

Thank you — glad to have you with us.

LikeLike