preface to the first edition of Autumn (18)

(Conclusion. Continued from part 2.)

But now, we leave behind the silly troubles of our age, the clouds gathered over our nonexistent future, the self-parodic incompleteness and defectiveness of our lives. We follow Huizinga into the stern, majestic world of medieval Europe.

Ostensibly, The Autumn of the Middle Ages is a historical monograph on the culture of France (especially Burgundy) and the Netherlands during the late medieval period. But what kind of academic study has ever begun like this?

(Autumn, 20-21)

The danger of writing about Autumn is that the book immediately takes over, brushing away my train of thought. Instead of discussing what Huizinga wrote, I only want to copy more and more of it, to withdraw and allow the book’s world to swell and efface my own feeble prose. The explosive imaginative power of Autumn naturally evokes the kind of reaction usually reserved for poetry — and, just as with poetry, translation issues assume a singular importance that they never have in other forms of writing.

Autumn was first translated into English in 1922 under the title The Waning of the Middle Ages. The beauty of Huizinga’s prose comes through in this version, but unfortunately the text was heavily abridged. Huizinga himself endorsed it, calling it “a work of adaptation, reduction and consolidation under the author’s directions,” but the true fascination of Autumn lies in the details and digressions, the tidal wave of imagery. A full translation (now titled Autumn) was then attempted in 1996 by two professors from Western Washington University, but unfortunately, completeness came at the expense of style. A third version appeared in 2020, now as Autumntide. Since the English-speaking world evidently cannot even figure out how it wants to translate the title, I decided not to bother with it at all, and instead rely on a Russian edition (Limbakh, 2016) for my page numbers.

You might think that this is a strange point to emphasize, but minor differences in translation sometimes change important nuances of meaning. For example, Waning translates the title of the first chapter as “The violent tenor of life,” while in the 1996 version this is given as “The passionate intensity of life.” In the first case, the reader expects a “critical” dissection of medieval brutality, something that hardly requires a 600-page treatise. The second case seems to foreshadow a depiction of hedonism and emotional excess. Both dimensions are indeed present in the text, but it seems clear that Huizinga is describing a much more total phenomenon. Brutality and hedonism are two manifestations of an overall hyper-magnified power of sensation. Something as routine as nightfall becomes intensely sensual. The world is alive. That is already a radical rethinking of the Middle Ages, which is conventionally viewed as a static, stagnant period, in which one’s every move was rigidly prescribed by tradition and clericalism. In fact, these two things give the world depth; without them, life becomes a two-dimensional caricature of itself.

Religion is repressive, you say? Tradition stifles individual desire? But there are passages in Autumn that veritably swoon with eroticism: “In the wearing of a handkerchief or an article of clothing belonging to the beloved lady — still retaining the scent of her hair or body — the erotic element of the chivalric tournament is made the most immediate. Excited by single combat, the ladies bestow one gift after another upon the knights: by the end of the tournament, they sit sleeveless and barefoot.” (139) From Huizinga’s time to the end of the 20th century, the destruction of the traditional ideal was motivated by the need to “free” the individual. What was most in need of “freeing,” according to this view, was the individual’s physical desire and instinct, which civilization had “repressed,” thus preventing the individual from reaching his full potential. What that potential was, no one knew, but it sounded good. Unfortunately, now that the brave new world has finally been built, it seems that there is no longer any use for the individual, and no one cares about his desires — having “freed” himself from society, he has become absolutely defenseless, and we are all about to find out what true repression is like.

But the world of Autumn has no trouble with desire and instinct: “Due to these omnipresent contrasts, these variegated forms of everything that touched mind and feeling, everyday life excited and inflamed passions that were made manifest one moment in unexpected explosions of crude unrestraint and brutal cruelty, the next in impulses of sincere tenderness — this mutable atmosphere was the life of a medieval city.” (21-22) Feudal loyalty could be driven by raw emotion as much as by law and tradition: “The young Charles the Bold, then still the Count of Charolais, arriving in Gorcum from Sluys, learns that the duke, his father, has seized all of his income and benefices. Chastellain describes how the count calls all of his servants, down to the scullions, and shares his misfortunes with them in a soulful speech… Let those who have the means to live remain with him, awaiting the return of his good fortune; as for those who are poor, they are now free: let them leave, but if they should hear that the count is again in Fortune’s good graces, ‘let them come back; and you will see that your places have not been filled, and I will greet you with joy and care for you, for you have suffered much for me.’ — ‘Then there were tears and laments, and in unison they cried: “We all, monseigneur, we all will stay with you, and with you we will die.“‘” (31) As Huizinga is quick to point out, this is a heavily stylized account, written by the official court historian of Burgundy…but it is a style that the medieval world itself created. It is emotional because that is what appeals to the heightened emotions of its readership. Nor are they lacking in creativity — the forbidding edifice of medieval tradition becomes a kind of art project designed to give beautiful expression to emotion and desire:

(Autumn, 140-141)

By the time period in which Autumn takes place, medieval chivalry had become a myth, if it had ever been anything else. But the nobility took great pains to preserve it in that form. Perhaps it was in service of their selfish ends, but as the next 500 years of history showed, virtually any idea can be used for such a purpose. The ideal of chivalry was no more self-serving than any other, and it could also be a double-edged sword for the authority of the nobility, because an integral dimension of its aesthetic was the lament over its decline. The retired lady-in-waiting Eleanor de Poitiers, commenting on the rules of etiquette, “sees them as wise laws, instituted at royal courts in ages past after careful deliberation, so that they may be revered in the future. She thinks of them as ancient wisdom: ‘and furthermore I heard the judgment of the ancients, who were learned…’ She sees signs of degeneration in her own time: for a good ten years, certain ladies in Flanders, when they are about to give birth, make their bed in front of the hearth, ‘which was once ridiculed’; this was never done before, and what good could possibly come of it? — ‘nowadays, anyone does whatever they want, which leads one to fear that soon things will truly go to ruin.'” (389) The dominance of this conventional wisdom can be seen from the fact that even this prosaic old lady expresses it. In upholding chivalry, one has to embrace the view that its glory days are long behind us — one follows tradition even though one cannot truly live up to it. Thus, to an enterprising, hot-headed young nobleman, tradition was no doubt a hindrance just as often as a help: a fine lineage gave you a great deal, but also raised questions of how well you live up to the standard set by your illustrious ancestors. The ruling class chose to keep propping up the ideal of chivalry long past the peak of its usefulness — not least, it seems, because they simply found it beautiful.

From The Book of Tournaments, by King René d’Anjou (1409-1480),

From The Book of Tournaments, by King René d’Anjou (1409-1480),

famous as an aesthete of chivalry.

The regalia and coloring had to be just right.

Everyone understood perfectly well the artificial character of the chivalric myth. To be sure, a few sincere enthusiasts of chivalry still remained:

(Autumn, 146)

But then, this level of detail is so over-the-top that it quickly takes on a parodic, make-believe quality; Mézières starts to sound like a teenager poring over the Dungeons & Dragons manual. In fact, he knew it too, and easily abandoned this silly plan as soon as he thought of a different one. Readers of Homo Ludens will have no trouble finding all the elements of a game in medieval chivalry. “From the mid-14th century, the establishment of [new] orders of knighthood becomes fashionable. Every ruler had to have his own order; the rest of the nobility was not far behind. This includes Marshal Boucicaut with his ‘Order of the White Lady and the Green Shield’ in defense of noble love and oppressed women; King John with his Chevaliers of Our Lady of the Noble House (1351), often called the Order of the Star due to its emblem… It includes Pierre de Lusignan with his Order of the Sword…Amadeus of Savoy with the Order of the Annunciation; Louis de Bourbon with the Order of the Golden Shield and the Order of the Thistle… In his travel diary, the Swabian knight Jörg von Ehingen demonstrates how orders of knighthood had acquired a resemblance to fashionable clubs.” (148-149) Gatherings of knights require sumptuous feasts, which are accompanied by elaborate and increasingly fanciful vows. “Vows are made during the feast; one swears by the bird that is served to the table and eaten… It seems likely that these vows were never originally addressed to divinity: and, indeed, often the vows are made only to the ladies and to the bird.” The arbitrary, overabundant detail of the vows is more than a little comic: “Here is a knight who will not sleep in bed on Saturdays until he slays a Saracen; also he will not stay in any one town more than fifteen consecutive days. Another one will not feed his horse on Fridays until he touches the banner of the Great Turk. Another one…will never wear armour, will not drink wine on Saturdays [Evidently, all other days are fine. -FL], will not sleep in bed, will not sit at a table, but will wear sackcloth.” (158) Clearly, everyone involved knew very well that he was playing a game, even though it would have been an offensive violation of the rules to say so openly.

The other great medieval myth, that of courtly love, was similarly theatricized, and yet, “The drive to stylize love was more than just a game. It was the powerful effect of passion itself that forced the fiery tempers of the late Middle Ages to elevate love to the status of a beautiful game, decorated by noble rules. If one did not wish to be seen as a barbarian, one had to confine one’s feelings within certain definite bounds…among the aristocracy, which felt itself more independent from the Church’s influence, since its culture lay outside the religious sphere to a certain degree, this sort of ennobled eroticism formed a barrier against debauchery; literature, fashion and custom helped bring order to the concept of love.” (185-186) One can always say that medieval culture, and really any culture, served a hypocritical purpose, providing a thin veneer over the brutality of everyday life. But one can also choose to see culture as the creation of a society aware of its own brutality, a ruling class that came to understand the need to impose certain artificial limitations on itself, to prevent its own urges from becoming totally uncontrollable.

At its best, the ideal of courtly love turned lust and desire into an elegant game, in which emotion and eroticism could be expressed (often very intensely) while protecting the parties involved. An especially striking example in Autumn is “the rather lengthy tale of poetic love between the elderly poet Gillaume de Machaut and the Marianne of the 14th century, Le livre du Voir-Dit (that is, A True Story). The poet was likely around sixty when a certain noble young lady from Champagne, Péronelle d’Armentières, being around eighteen years of age, contacted him in 1362 with her first rondel, in which she offered her heart to the famous poet whom she had never met, and asked him to enter into an amorous correspondence… He answers her rondel; there begins an exchange of letters and poems. Péronelle is pleased with her literary connection, from the start she makes no secret of it. She wants him to truthfully describe their love in his next book, in which both the poems and the letters are to be included.” But Péronelle is not satisfied with purely epistolary romance and soon demands to meet Machaut in person. Taking advantage of a religious holiday to arrange their rendezvous, they “find shelter in a private home, whose owner offers them a room with two beds. In this bedroom, shaded for midday rest, Péronelle’s sister-in-law takes one bed; Péronelle herself occupies the other together with her maid. She orders the indecisive poet to lie down between them, and he remains as motionless as a dead man, afraid to cause her the least inconvenience; when she awakens, she orders him to kiss her.” Huizinga comments, “First of all, one has to note the incredible freedom afforded to a young girl, with no regard for what others may think. Then — the naive nonchalance with which everything, down to the most intimate scenes, occurs in the presence of outsiders, such as Péronelle’s sister-in-law, maid, and secretary. During a rendezvous in the cherry orchard, the last of these plays a lovely trick: when Péronelle falls asleep, he covers her lips with a green leaf, telling the poet that he may kiss this leaf. When he dares to do so, the clever secretary quickly removes the leaf, so that Machaut kisses her directly on the lips.” The charming frivolity of these scenes may give the impression that Machaut was a purveyor of sugary love poetry, but in fact he was among the most illustrious artists of his day, having authored the earliest known complete musical composition of the Catholic Mass, and to him, the affair with Péronelle was the most important event of his life. “The expression of emotion is couched in expansive, verbose passages, allegorical fantasies and dreams. There is a touching quality in the sincerity with which the aging poet describes the magnificence of his happiness and the amazing perfection of his Toute-belle, failing to realize that, in essence, she is toying with his heart as well as her own.” The gravity with which he approaches the subject, however, indicates that he understands all too well that he is being used in this manner, likewise that it cannot last. Indeed, eventually “Péronelle tells him that they must sever their ties — likely due to her impending marriage.” (209-213)

I shudder to think how this affair might play out in our time. It would truly be a subject for Nabokov’s poison pen — indeed, what is Lolita but the logical conclusion of absolute aesthetics unfettered by any ethical sense? The hapless lovers would soon rip each other apart, the demons of modernity whispering in their ears, urging them to stop at nothing in service of their egos. Not to say that those same motives were not present in the 14th century; it is not hard to see Péronelle’s selfishness, her arrogant confidence in the power of her charm, her curiosity about how far it can be made to go, her amusement at having this accomplished poet grovel at her feet. No doubt Machaut’s thoughts of her were not limited to poetry, either. And yet, the form saves the content. Péronelle walks away with idyllic memories of having once been a fairy-tale princess, which no doubt became a source of great comfort to her later, after many dull years; and Machaut accepts the bittersweetness of the affair as well as its inevitable conclusion, remaining grateful that this unreal romance had come to illumine his old age.

As a greater whole, however, the late Middle Ages had achieved such mastery of this form as to become aware of its artifice. Satire and subversion were also a natural part of the myth. This philological sophistication can be seen in the Roman de la Rose, a novel-in-verse composed, unusually, by two authors, working about 45 years apart, in the 13th century. The first author, Guillaume de Lorris, fully accepted the ethos of courtly love and sought to write an elegant allegorical poem within this idiom. “His graceful design is accompanied by lively, charming fantasy in the development of the storyline… On an early morning in May, the poet goes outside to listen to the singing of the nightingale and the wren. He walks along the river and finds himself at the walls of the mysterious castle of love. On the walls he sees images of Hatred, Perfidy, Boorishness, Avarice, Miserliness, Envy, Despondency, Old Age, Hypocrisy and Poverty — all qualities that are alien to courtly life. Yet Lady Idleness, a companion of Joy, opens the gates. Inside, Merriment leads a dance… The poet swears fealty to Love; Amour unlocks his heart with his key and introduces him to…the woes and blessings of love.” (193-194) Several decades later, however, a certain Jean de Meun revisited the work, obviously without the original author’s permission, increasing its length fivefold and introducing a rather different tone: “we see a man whose unaffected spirit, cold scepticism, and cynical ruthlessness were rare for the Middle Ages… The naive, bright idealism of Gillaume de Lorris is now shadowed by the nihilism of Jean de Meun, who believes neither in ghosts and wizards, nor in faithful love and woman’s honesty; who understands the painful problems of his time and…decisively defends the passionate vitality of life.” As a part of that, for example, de Meun brings in Venus, who “swears that she will never again tolerate any woman to be chaste, urges Amour to make a similar promise regarding men,” (195) leading to a blatant parody of Roman Catholic ritual in which virginity is “cursed.” In doing this, de Meun aimed, not to attack or question the ethical norms of medieval society, but simply to justify the pursuit of hedonism as a unique privilege of those who have the proper upbringing. “The garden of earthly delights is accessible only to the elect and only through love. The positive virtues…emphasize that the ideal is now becoming purely aristocratic, losing the ethical character of courtly love. These virtues are nonchalance, pleasure, good cheer, love, beauty, wealth, generosity, free spirit and courtliness. These qualities no longer help one to be ennobled by the light emanating from one’s beloved; rather, they are instruments used to conquer her. The spirit of the work is no longer reverence (genuine or not) for woman, but…cruel contempt for her weaknesses; a contempt whose source is the very sensual nature of this love.” (197) Medieval misogyny was formed as a worldview only when medieval culture began to break itself down; it was born of licentiousness rather than tradition.

The second edition of the Roman de la Rose was unsurprisingly very popular in its day (part of it was even translated into English by Geoffrey Chaucer), but also provoked rather strong opposition. Some of it came from religious moralists, but one’s attitude toward the work was determined more by one’s personal intellectual outlook than by one’s social status — thus, Jean de Montreuil, Father Superior of the Cathedral of Lille, defended the Roman on purely secular, aesthetic grounds, and on the opposing side, theologian Jean Gerson found an ally in court lady and accomplished writer Christine de Pizan: “All of these conventional forms of expressing love are the work of men… What are these oft-repeated statements about marriage and feminine weakness, inconstancy and frivolity, but a cover for male selfishness! To all these reproaches, says Christine de Pizan, I will say only that none of these books had been written by a woman.” (231) But that does not mean that no books were written by women: Christine de Pizan was herself an admired author of love poetry, as well as court history and moral tracts. The debate over the Roman also had a dimension of intellectual competition and literary aesthetics. Through its dual-author structure, ambiguity was built into the book; in a sense, it was always intended to be an ornate curio on which a sharp mind might demonstrate its intellectual sophistication, from any side of the issue.

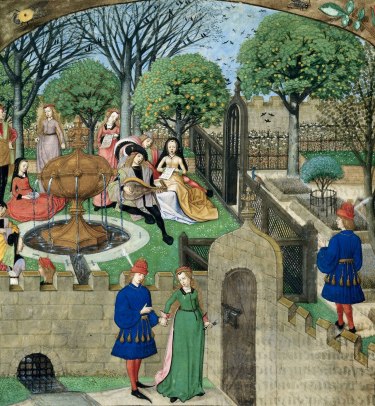

From a 15th-century manuscript of the Roman de la Rose.

From a 15th-century manuscript of the Roman de la Rose.

It goes without saying that this courtly contest between the sexes transpired exclusively within the aristocracy. The rest of the population, including even its richest members, was shut out from this beautiful culture:

(Autumn, 105)

But then, if you came all this way to tell me that, I don’t suppose that you are one of our present-day serfs either — perhaps a single mother living in Dallas, working two jobs, stuck with a broken air conditioner in mid-July. Medieval oppressors were more public than today’s faceless old men in suits (or aprons), which also made them more vulnerable: “Often the condemned were nobles, and then the people obtained even livelier satisfaction from seeing justice done, an even crueler lesson of the frailty of earthly power, than could be had from any graphic depiction of the Dance of Death. The authorities never missed a chance to make the greatest impression with this spectacle: the condemned were accompanied by all the signs of their high office during their sorrowful procession [to the gallows].” (24) And one cannot say that the aesthetic element was completely absent from the lives of the lower classes: “When…King Charles VI unfurled the Golden Flame in 1412, to set forth with John the Fearless against the Armagnacs, who betrayed their homeland by forming an alliance with England, it was decided in Paris to hold a procession every day that the king stayed in hostile lands. They continued from late May almost to the end of July; every order, guild and corporation had its turn to participate; each time they went along different streets and carried different relics: ‘most piteous processions, you will not see anything more sorrowful as long as you live’. In those days the people fasted; all went barefoot — councilors of Parliament as well as the poorest city folk; the able-bodied all carried torches or candles; children were always among them. Poor farmers walked to Paris barefoot from far away. People either took part or observed those who walked ‘with great weeping, with great sorrow, with great awe.'” (22-23)

Huizinga’s cited source in this passage is a document called Journal d’un bourgeois de Paris, a diary from the early 15th century whose anonymous author reflects on current events from a common-man perspective. Among other topics, the journal extensively comments on the trial of Joan of Arc, to the extent that an ordinary (if literate) Parisian could do this, seeing as the available information consisted mostly of hearsay; thus, the stolid bourgeois quickly assures himself that “my lady Jeanne’s false errors…were all declared to her in front of the people, who were horrified when they heard these great errors against our faith which she held and still did hold. For, however clearly her great crimes and errors were shown her, she never faltered or was ashamed; but replied boldly to all the articles enumerated before her like one wholly given over to Satan,” and finally reaches the rather unsatisfying conclusion, “whatever good or whatever evil she did, she was burned that day.” The majority opinion among 19th-century academics was that the author must have been a priest, yet his knowledge of theology and Church affairs is no deeper than his thoughts on current events; perhaps he was a low-ranking clergyman or official, primarily occupied with day-to-day household concerns. But while he may have been completely unequipped to understand the events of his time, his incomprehension made his reactions all the more striking when disaster struck close to home. “During the most terrifying scenes of murder and looting, the victims were usually left their shirts and underpants. The Parisian bourgeois is especially appalled when this immutable rule is violated: ‘and their greed did not allow them to leave [their victims] even their pants, even if they had cost but four deniers — which was one of the greatest cruelties, an inhumanity inexcusable for Christians, that was ever heard of.'” (Autumn, 535) But this horrible catastrophe, namely “the massacre, perpetrated by the Bourgignons in June 1418, that filled Paris with the same smell of blood as September 1792,” has the effect of elevating the good man’s prose style. He writes, “Then arose the goddess of Strife, who dwelt in the tower of Evil Counsel, and awakened vehement Wrath, and Greed, and Fury, and Vengefulness, and they all took up arms and most shamelessly struck down Reason, Justice, Piety and Moderation.” Huizinga comments: “Why is there a need for allegory? So that the author may fulfill his wish to rise above the level of everyday occurrences, which he usually writes about. He feels the need to look at these terrible events as if they arose from something greater than mere human intent, and allegory serves as an expressive medium through which he understands the tragic.” (357-358)

“The Dance of Death,” Michael Wolgemut, 1493.

“The Dance of Death,” Michael Wolgemut, 1493.

Medieval violence imposed a dark fatalism onto the medieval aesthetic. The flip side of the romantic dream of courtly love was the twisted imagery of the Dance of Death, the concept of the “macabre” (a strange word of poorly understood origins). Not only was this a popular subject for individual works of art and moral literature, but many cemeteries, mausoleums and religious sites were “decorated” entirely in this style: “…The Dance of Death at the Holy Innocents’ Cemetery, which was destroyed in the 17th century when the entire gallery collapsed, was the most popular depiction of death among all that the Middle Ages had ever known. In this strange, macabre place…day in and day out, thousands of people saw these unsubtle images, gazed at them, read simple and memorable poems, whose every verse ended with the usual saying [Some version of “remember death.” -FL], and trembled before their inevitable end, comforting themselves with the reminder that all are equal before the face of Death…[which] swept along popes, emperors, knights, craftsmen, monks, children, jesters, and all other classes and professions.” (246) The Holy Innocents’ Cemetery, dismantled in 1786, was a truly bizarre cultural icon of medieval France. Here, death was flaunted exhibitionistically, using the most grisly imagery that medieval minds could come up with: “The crypts in the upper parts of the galleries, which surrounded the cemetery from three sides, were piled full of skulls and bones: by the thousands, they gleamed with whiteness, open to public view, demonstrating a clear lesson of universal equality… Among others, Marshal de Boucicaut donated money for the construction of these ‘beautiful crypts.’ The Duke of Berry, who wished to be buried in this cemetery, arranged for the church entryway to be decorated with a sculpture showing three dead men… Later, all the way in the 16th century, an enormous statue of Death was installed here; it is now on exhibit in the Louvre, being the only surviving remnant of this place and all that it once contained.” But you underestimate medieval people if you think they only came here to weep. Ever cheerful, Parisians turned this place into a ground for social gatherings and romantic outings. “Among the endlessly filled and excavated graves, people went on strolls and arranged rendezvous. Merchant stalls huddled by the crypts, and the arcades were frequented by women who were not known for their particularly strict morals. And one couldn’t do without a reclusive nun, sealed in her cell by the church wall. Sometimes a mendicant monk would preach at the cemetery… Festivities were held there as well. So much had the awe-inspiring become routine.” (252-253)

Perhaps you expected something less graphic.

Perhaps you expected something less graphic.

In one of Huizinga’s interpretations, medieval people were so attached to earthly life that they couldn’t bring themselves to accept its impermanence: “Undoubtedly, all of this was permeated with crude materialism, which cannot come to terms with the notion that something beautiful must perish without doubting beauty in and of itself.” (239) I would suggest looking at this idea from a slightly different angle — beauty is, to some extent, a spiritual concept, and the “crude materialism” of the medieval attitude toward death is, at its core, completely atheist, despite all the religious accoutrements of the Holy Innocents’ Cemetery. The anti-aesthetic of the macabre is an integral part of the overall hypertrophied sensuality of the medieval world. Religion, like food and entertainment, could only be experienced physically. It was in the Middle Ages that Roman Catholic mysticism developed its peculiarly fleshly character: “The intrusion of the divine is experienced in the same way as the satiation of hunger and thirst. One adherent of the new piety from Diepenveen feels as if she is being drowned in the blood of Christ, and faints. Coloured with blood, these fantasies…find their expression in intoxicating visions from beyond the grave, seemingly illuminated by a scarlet glow. The wounds of Christ, according to Bonaventura, are the blood-red flowers of our sweet, blossoming paradise, in which the soul will taste nectar, flying from one flower to another like a butterfly… Catherine of Siena was one of the saints who fell to the holy wounds and drank the blood of Christ, just as others had occasion to taste milk from Mary’s breasts: St. Bernard, Henry Suso, Alain de la Roche.” (339)

A widespread view is that the Protestant Reformation was a rebellion against the excesses of the Roman Catholic Church, e.g., the corruption and hypocrisy of its clergy. But really, in the grand scheme of things, that was a minor irritant at most; there are hypocrites and simonists in any religion. The truly existential issue for Roman Catholicism was that pious Catholics expressed their sincere religious aspirations, even formulated their innermost thoughts about God, using this same sensual language of physical intoxication and desire. The sale of indulgences would never have gotten as far as it did if there hadn’t been so many willing buyers. The crypto-pagan attitude toward religion, which Huizinga accurately calls “the insufficiently Christianized folk perception,” (299) was not imposed from above by corrupt hierarchs, but rather swelled from below, from the great mass of the population; many clergymen embraced it, but only because most clergymen also originated from that same bottom layer. There are genuine Catholic scholars and sincere ascetics roaming the pages of Autumn, but their voices drowned in the tide.

The Reformation attempted to restore religious sobriety by changing the language in which religious thought and feeling were expressed. Perhaps our present-day conception of Protestantism and Catholicism does not accurately reflect their original relationship; perhaps they used to be much closer, and Protestantism originated as a theological trend within Catholicism — at least, some of the theologians in Autumn, all Catholics through and through, would not have minded some mild Protestantization of the unruly folk religion. Of course, if this had been the case, it would only have amplified the violence of the disagreement, not unlike how, in the 8th century, Christian theologians saw Islam as a Christian heresy (which is how St. John Damascene describes it). But, in any case, just like the stylized language of courtly love, the fanciful and image-rich language of the church served as a restraint on baser instincts; once it was gone, it only took a couple hundred years to reach the conclusion that there was no need for God at all. Ultimately, what Western people have always wanted is not salvation and eternal life, but self-gratification, in its most crude physical sense — perhaps that is the one thing that they still have in common with their medieval ancestors. Modern culture devours itself just as its medieval predecessor had. Decadent writers in fin-de-siècle France were so satiated with all forms of debauchery that they began to aestheticize death as a kind of ultimate high, which they experienced or imagined in a rather “macabre” form, rotting alive from venereal disease and alcoholism. Likewise, every present-day aberration of the Western psyche plays the same role as the medieval cult of Death, the decaying corpses placed proudly on display in the Holy Innocents’ Cemetery.

But, for all its ugly aspects, one cannot deny that medieval vitality also possessed great seductive power. Huizinga’s stated goal in the preface of Autumn is to show an age in decline, but the book has the exact opposite effect. Yes, the medieval aesthetic was becoming obsolete, but even in its final moments it shows no sign of letting up. A recurring character throughout Autumn is the 15th-century Dutch painter Jan van Eyck, whose work gives Huizinga countless topics to ruminate over. Here is one of his paintings, commissioned by Nicolas Rolin, chancellor to the Duke of Burgundy:

“The Madonna of Chancellor Rolin,” Jan van Eyck, 1435.

“The Madonna of Chancellor Rolin,” Jan van Eyck, 1435.

At first glance, this looks exactly like what we are conditioned to expect from medieval painting — excessively formal, servile toward its subject (who is, of course, the Chancellor, not the Madonna), and hypocritical in its opulent display of what is ostensibly supposed to be piety. The Virgin Mary here serves the same purpose as Rolin’s luxurious clothes — having her as his personal Bible study partner is just another status symbol. On top of that, even Rolin’s contemporaries knew that he was about as ill-suited to this perfect image as could be imagined; Chastellain wrote, “He always reaped his harvest on earth only…as if the earth had been given to him, in perpetuity, for his personal use; such was his error, for he set no limit, no boundary to what his declining years were telling him would soon end.” (454) Even on the painting, his face looks cynical; who knows, maybe that is what van Eyck intended.

But just outside Rolin’s chamber, the world teems with life:

(Autumn, 478-480)

Perhaps Dutch pride was behind Huizinga’s wish to see in van Eyck the highest expression of medieval culture. But it does not really matter whether van Eyck is “the greatest” in whatever sense, since overabundance of detail does not necessarily have to be an aesthetic triumph — in fact, Huizinga often sees it as a failure: “The main distinguishing feature of late medieval culture is its excessively visual character. This is closely connected to the atrophy of thought. One thinks only in visual representations.” (489) Van Eyck only serves as an illustrative example of how the sensual world forcefully intrudes into even the most rigid forms of medieval art.

In that respect, there is no real difference between medieval and Renaissance art. In the latter, the medieval impulse to overload the artistic subject with physical sensation finally gets its chance to run wild:

According to Michelangelo and Pope Julius II,

According to Michelangelo and Pope Julius II,

this grand display of flesh is very Biblical.

As Autumn goes on, the distinction between the Middle Ages and the Renaissance becomes increasingly tenuous. While the book is full of references to “faded symbolism” (that is the title of Chapter 15 — Waning renders it as “symbolism in its decline“) and the like, by the end it seems that those aspects of medieval culture that indeed became obsolete were only of secondary importance. The Renaissance no longer looks like a break, much less a deliberate one, with medieval culture. The debate over the Roman de la Rose, in which scholarly theologians defended the book on aesthetic grounds, is clearly an early harbinger of, not even the Renaissance, but the Enlightenment: “This polemic uniquely shows how French humanism sprouted within a circle which believed itself to be defending a fanciful, sensual, truly medieval work. Jean de Montreuil is the author of many letters in the Ciceronian style, rich in humanistic phraseology, humanistic rhetoric and humanistic vanity.” (199) These same people were all well-acquainted with Greek and Roman literature and wrote to each other in Latin — so much for the Renaissance’s “rediscovery” of ancient culture. And Enlightenment philosophy, despite its outwardly rational appearance, really grew out of medieval occultism: “In [Meister] Eckhart’s mysticism, Christ is almost never mentioned, to say nothing of the church and sacraments.” (374-375) Freud and Jung were totally medieval in spirit, and would have felt perfectly at home in the 14th century as self-proclaimed alchemists and wizards, which is exactly what they were.

The Western world did lose something with the passing of the Middle Ages, but it cannot be measured in terms of aesthetic taste or literary technique. Deep down, humanity did not lose its violent lust for life, but perhaps it lost the capacity to extract any real joy from it. Courtly etiquette was a social regulator and a status symbol, but it was also a source of pleasure; its intricacies made everyday life enjoyable. The wildness of the folk-religion was brightened, if not by sincere love for God, then at least by the joy of the religious holiday. The aristocracy may have only pretended to embody the virtues of chivalry, but at least the game encouraged “a cheerful courage, which helped one to cope with adversity and withstand danger.” (127) Or maybe the real value of chivalry was not in its ethical specifics, but simply in the fact that it was an ethical ideal — what Huizinga called a “historical ideal of life” in his first lecture at Leiden in 1915. The existence of such an ideal makes the universe habitable, creates a place for humanity in it. When order is brought to human life, only then does the possibility of harmony and proportion first appear. Every human individual obtains a place and an aspiration to fulfill, which may be different from what the ideal originally intended — as Huizinga pointed out in the same lecture, “All the higher forms of bourgeois life in later times have actually been based on the imitation of the ways of life of the medieval nobility… Courtly life and the courtly concepts of virtue and honour served to produce the modern gentleman.”

At some point, Autumn evinces certain indirect parallels to another medieval vision from the 20th century, namely The Lord of the Rings. Tolkien undoubtedly read Autumn, out of professional obligation if nothing else. We should not overstate the similarity between a historical monograph and a fantasy novel…but perhaps Tolkien’s desire to finely sculpt all the tiny details of Middle-earth was a reaction to that same excess of detail in the material from which he drew inspiration. In a certain sense, Tolkien is a modern Jan van Eyck, right down to the somewhat stiff forms in which his prose is confined. As the narrative progresses, the folksy, old-fashioned but familiar countryside air of the Shire dissipates, the green rolling hills of England are transformed into the harsh wilderness of ancient Europe, while the high prosody of Old English and Old Norse creeps into the author’s voice. Tolkien attempted to create a world where medieval heroism and courtliness (the latter represented by Galadriel, an exemplary “beloved lady” from chivalric romance) could still be alive, just as Autumn does by reconstructing the real world where they once lived. And, in the end, what is The Lord of the Rings but a story of the “waning” of an age, concluding with its great heroes sinking into oblivion, just as their prototypes in medieval history had?

“The Accolade,” Edmund Leighton, 1901.

“The Accolade,” Edmund Leighton, 1901.

Tolkien’s feminine ideal came from the same source.

But if one approaches Autumn as literature, it makes fiction look anemic in comparison. From its first pages, Autumn explodes with imagery — scenes of processions, public sermons, executions, intrigues, which are not only described in primary sources, but also commented on by the authors of those sources, themselves historians, theologians, courtiers. These people themselves become “characters” that appear many times throughout the book to offer opinions on the central theme of each chapter, creating the impression that they are talking and responding to each other. The official court historian of 15th-century Burgundy is mentioned perhaps three dozen times in the text before Huizinga officially introduces him all the way in Chapter 20: “There is one author whose writing touches us with the same crystalline clarity of vision of the outward appearance of things that we saw in van Eyck; that is Georges Chastellain. He was Flemish, born in Aalst. Although he called himself ‘a true Frenchman,’ ‘a Frenchman by birth,’ it seems that his native tongue was Flemish… With rustic self-satisfaction, he flaunts his Flemish qualities and his country manners; he mentions ‘[his] crude tongue,’ calls himself ‘a man of Flanders, a man from the swamps where sheep graze, a mumbling ignoramus, a glutton, a villager, with all the bodily vices of the place of [his] birth.'” (Autumn, 489-490) Huizinga then cites some of his writing in order to discuss its artistic merit, but since Chastellain was also writing about history, his own person retreats into the background and a completely different image unexpectedly coalesces and seizes total control of the narrative: the young Count of Charolais, future Duke of Burgundy, argues with his father over a court appointment.

(Autumn, 492-493)

These extracts continue for another two pages, far longer than would be necessary for a purely academic treatment of Chastellain’s writing. Although Chastellain wrote this passage, from the point of view of the reader of Autumn he is just as much of a literary personage as Charles the Bold. In fact they are both simultaneously historical and literary figures, since Charles is a character in Chastellain’s book, while Chastellain himself is a character in Huizinga’s. Then which of them are we really studying? What are we really studying in this chapter, which purports to offer a comparison of descriptive detail in painting vs. literature?

Evidently, Autumn is not an academic monograph at all — it is a philosophical novel, which uses the fabric of historical sources to assemble a dialogue between its characters. The author himself participates by using his thoughts to give direction to the narrative, but ultimately the goal is not to make scholarly arguments, but to build a living, breathing world. In this respect, the world of Autumn is infinitely more vibrant than any fictional world, because it has the ability to reflect on itself — an ability conspicuously lacking in Middle-earth, and even in fictional “extended universes” of the kind that are created by large numbers of commercial authors working over several decades. Each theme in Autumn already comes with dozens of individual viewpoints, some of them already aware of each other, others forced to come in contact by the author. Many of them linger long after having made the point Huizinga put forward, as if there were something more that they still wanted to say. Burgundian courtier Olivier de la Marche, having been brought onstage to tell a brief anecdote illustrating the omnipresence of hierarchy in court life, is reluctant to leave, and continues to fret over the fine points of etiquette: “When I was a page…I was still too young to truly understand questions of priority and distinguish between ceremonial subtleties. …Why does the head cook attend at his lord’s meal, instead of a scullion, that is, the master and not the apprentice? How is the head cook appointed? Who should substitute for him when he is away — the master roaster, or the master soup-maker?” (78) Any writer of fiction always struggles with the problem of plausibly depicting someone else’s point of view, for which reason many great writers simply gave up on the idea entirely and focused on writing about themselves. The variety of viewpoints in Autumn is far beyond any writer’s ability.

Huizinga would have objected to such a view of his book. In a 1929 article titled “The task of cultural history,” he cautioned against an excessively “literary” treatment of history, which “stems from a literary need, works with literary means, and aims at literary effects.” But elsewhere in the same essay, he proposes an approach that seemingly cannot do without some sort of literary dimension:

from “The task of cultural history”

But the inevitable conclusion is that this effect, in which Huizinga sees the greatest possible achievement for history as a scholarly discipline, requires there to be a writer. History is obtained from historical sources (Huizinga repeatedly stresses the importance of rigor in historical research), but it is not simply their combined content. History is created at the moment of contact with those sources by someone outside them — a historian, a student, a reader hundreds of years later. This contact is reciprocal: in a certain sense, the historian retroactively influences the past. Through the historian, the past is finally able to speak its mind; what had been scattered across hundreds of documents and artifacts coheres, for the first time, into a single, clear statement. Perhaps the Middle Ages only truly came to life in 1919, on the pages of Autumn.

Creators of art and literature hope that their work will outlive them. But culture is not immortal either; there comes a time when posterity just does not care anymore. Medieval painting has found its last refuge at museums, and medieval literature has disappeared completely — at best, some of it is available in fragments or in summary form, unless one is a very narrow specialist with access to university archives. Yet, strangely, the people who originally put meaning into these obsolete forms have found new life as characters in Autumn. It has become more difficult to send them back into nothingness. In “The task of cultural history,” Huizinga comments on many then-contemporary historians, citing many of them with great respect. Very few of these people are still in print; only Jacob Burckhardt and Henri Pirenne escaped this common destiny, being exceptions that prove the rule, half-historians and half-philosophers with considerable literary gifts. Everyone else is, for lack of a better word, dead. But Autumn is alive and well one hundred years later — all three English translations are readily available. History dies when the living generation turns away from it, but the dialogue resumes as soon as the book is reopened, even by a single person. Culture can die, but it can also be reborn.

I sometimes tell people it was Wendell Berry’s literary essays that taught me how to read. I mean really read, with purpose and depth. This blog of yours is having a similar, perhaps even broader, effect. Thank you.

LikeLike

Thank you — glad to have you with us.

LikeLike